technological utopians

an interview with Michael Stern (1970)

TECHNOLOGICAL

UTOPIANS

an interview with Michael Stern (1970)

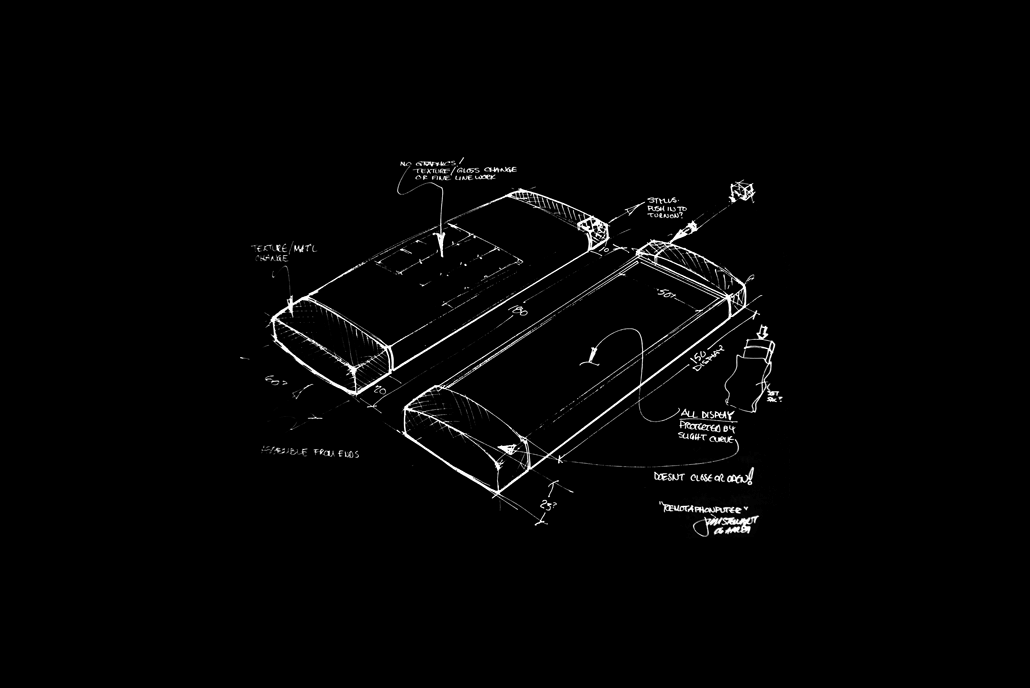

General Magic premiered at the Tribeca Film Festival on April 20th, 2018. The film tells the story of an ultimately-doomed Silicon Valley start-up, which, in the mid 1990s, was developing the world’s first smartphone, and many other technologies that we now rely on, a decade before the launch of the Apple iPhone. General Magic, which began as a spin-off from Apple itself, counted amongst its staff people who would go on to become giants of the tech industry in their own rights.

The film combines archival documentary footage filmed during the company’s rise and fall in the 1990s, with candid present-day interviews with the former ‘Magicians’ (as the employees came to be known).

Michael Stern (1970), a former Clare Kellet Fellow, acted as general counsel for General Magic between 1991 and 1995, and was the film’s executive producer. Here, he tells us more about the extraordinary atmosphere surrounding General Magic during its highest and lowest points, and reflects on the film’s development.

How did directors Sarah Kerruish and Matt Maude approach you about being a part of the film? Did you require any convincing?

It was somewhat the other way around. I knew that we had the archival footage (Sarah was one of the crewmembers who originally shot it) and Sarah and I talked every couple of years about using it to make essentially a home movie for the Magicians. We finally got started in 2013; Sarah met Matt a year or so later when we were still at the written treatment stage and he told us we were missing the point. We had a real commercial documentary on our hands and needed to get serious. With his invaluable help and creative energy, we did.

Michael Stern, left, with directors Matt Maude and Sarah Kerruish

Michael Stern, left, with directors Matt Maude and Sarah Kerruish

Why did you think this was such an important story to tell?

I originally thought it was principally part of the social and technical history of Silicon Valley, something I’m deeply interested in—the backstory of the iPhone, etc.—but came to see it as primarily a human story about failure and redemption, and a universal story of the hero’s journey: those of the kids who came to work at General Magic going on to do such extraordinary things.

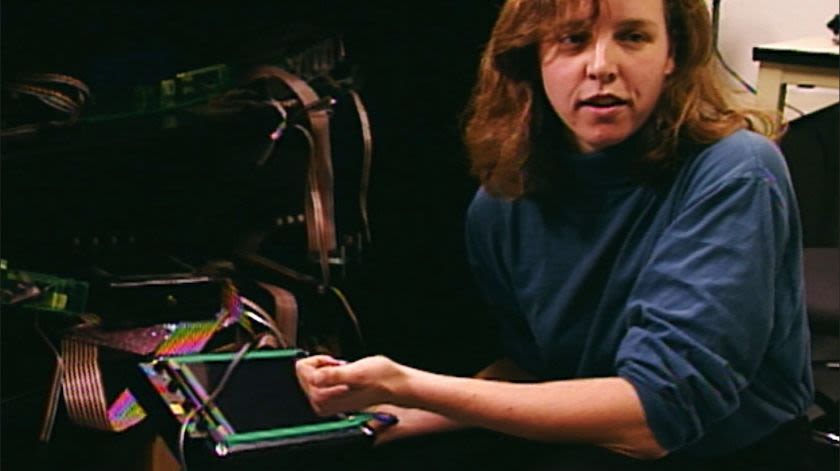

Engineer and Magician Megan Smith, who went on to become VP of Google, founder of Planet Out, The Malala Fund, shift7 and White House Chief Technology Officer under the Obama Adminstration.

Engineer and Magician Megan Smith, who went on to become VP of Google, founder of Planet Out, The Malala Fund, shift7 and White House Chief Technology Officer under the Obama Adminstration.

What was a high point of the filmmaking process for you?

When we started doing the interviews and people started to say amazing things—it was like when you’re writing a news story and the lead just audibly clicks in your head. We knew we had a story, and the people to tell it.

Software engineer Andy Hertzfeld testing a prototype at General Magic.

Software engineer Andy Hertzfeld testing a prototype at General Magic.

You came to Clare from Columbia as a Kellet Fellow, and afterwards began your career as an English professor at Harvey Mudd College in Claremont, CA. Can you describe your journey from there, to being involved with General Magic and the tech industry?

It was pretty random, like most careers. My wife was seriously ill, and our HMO [health maintenance organisation] in Claremont used up its treatment options. Stanford had an experimental protocol in the works, so we moved to Palo Alto so she could get into the trial. I commuted to Claremont for a year, but that just wasn’t working, so I quit and started working as a marketing guy for a little computer company in the Valley (my journalism experience as a Washington Post and Wall Street Journal reporter helped with that). Our son was in day care at the Jewish Center in Palo Alto, and lots of the kids in his class were the children of other ex-academics who had come to the Valley to start companies, or of lawyers in town who had them as clients at one of the local firms. So I sort of knew where I wanted to work before going to law school at Berkeley.

After I graduated in 1983, I ended up at the firm where these parents all were, and they were my first clients. My firm did the work opposite Apple (our big competitor did the Apple work), so Apple’s general counsel came to us and asked if we would do the Magic spinout. It was incredibly intense getting the company rolling and I ended up doing it pretty much full time, so it seemed natural to accept Marc’s [Marc Porat, General Magic’s CEO] invitation to join the team a year into it. I was very lucky.

Marc Porat, CEO and Founder of General Magic

Marc Porat, CEO and Founder of General Magic

The film paints a picture of the years between 1990 and 1995 for General Magic as being something of a blur, with employees regularly working 80 hour weeks and sleeping in the office to get the job done. Do you have a particular memory from the time that sums up that atmosphere?

One of my jobs was helping Marc with Alliance Management—trying to keep our 16 strategic investor companies (all of the big international telephone companies and consumer electronics giants) aligned. Some were in Europe and some in Asia. I had to talk to the Europeans early in the morning California time, and to the Japanese late at night. So, when we were trying to get them all to do something, I would just sleep at the office, and then stumble home for a while in the afternoons.

Something we didn’t put in the movie: at the 1993 New Year’s party (which has a scene in the film, where people are playing with balloons), the crew filmed each member of the management team and their spouse or significant other saying “Happy New Year” to the Magicians. Every one of our partners, unrehearsed, looked at the camera and said: “Will you please hurry up and finish the damn thing and come home?” But we still had over two years to go.

Did you always have the sense that the people you were working with would go on to achieve great things?

It dawned pretty early that they were an extraordinarily talented bunch and were just getting started.

Have you stayed in touch with any of the other former Magicians?

Yes—with lots. The friendships you forge in a cauldron like that are for life.

How would you describe life after General Magic? Did the launch of the smartphone in the 2000s change your perspective on the experience?

We were classic Valley technological utopians—creating a magic tool that would enable people to connect with each other and the world would be liberating, we thought. Our legacy—our Apple DNA—was the democratisation of personal computing that the Macintosh had enabled. What we missed was the dark side—that those same tools could be instruments of oppression and alienation, making us vulnerable to the national surveillance state, psychographic manipulation and microtargeting by the

platforms and their sometimes nefarious users (like Russian disinformation ops), and the attrition of our attention spans and loss of real personal connection.

You recently returned to Clare to host a special screening with the directors. What was that like?

It was a joyful experience. My original time in Cambridge was also my honeymoon (my wife and I got married just before we sailed) and a glorious time of intellectual growth (I got to work with Raymond Williams, Stephen Heath and Tony Tanner, among other great teachers). Reconnecting with Clare and having such a terrific audience at the screening was really fun. Thanks to you and Bill and the team for that!

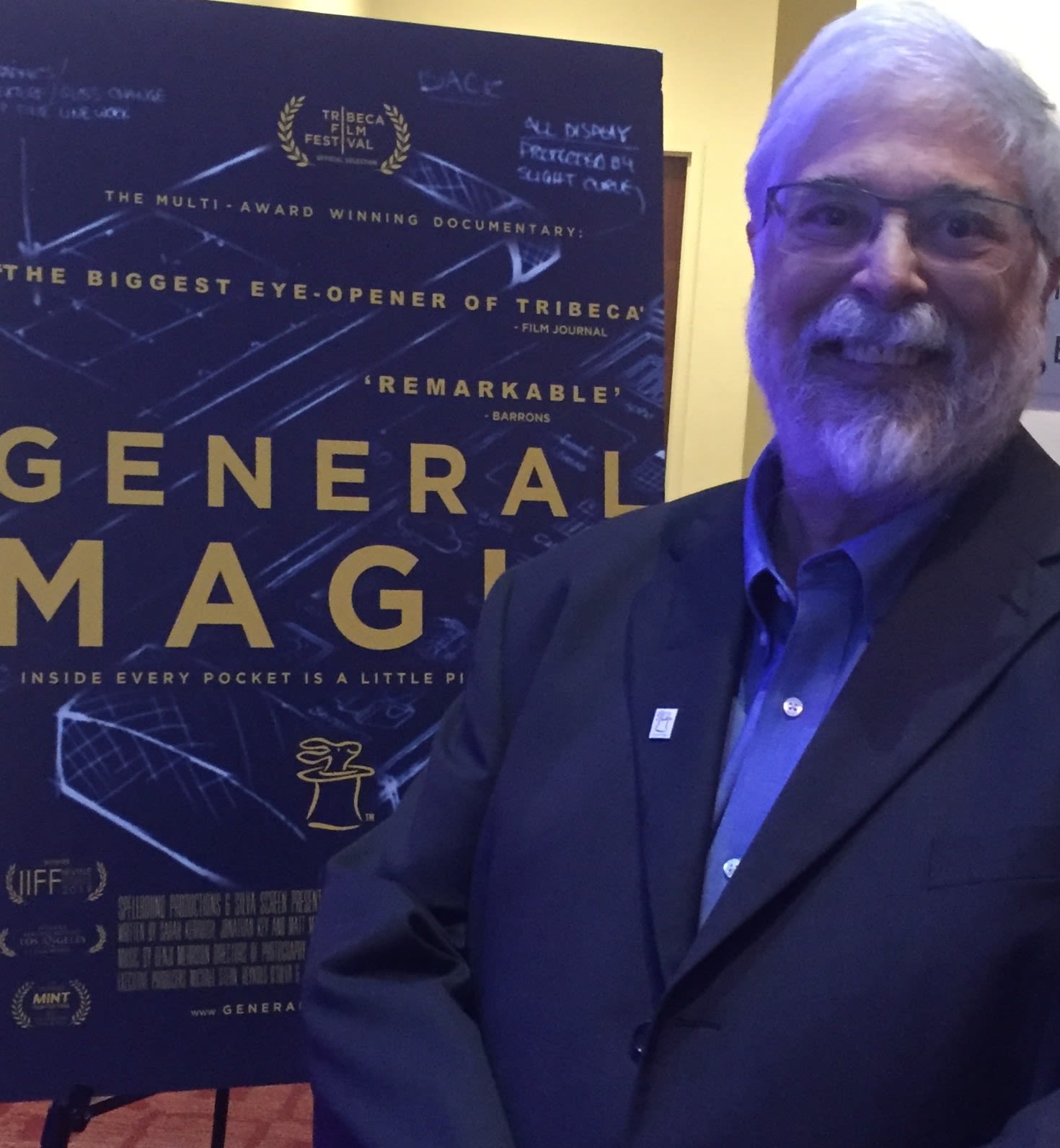

Mike at the Clare screening of General Magic in 2019.

Mike at the Clare screening of General Magic in 2019.