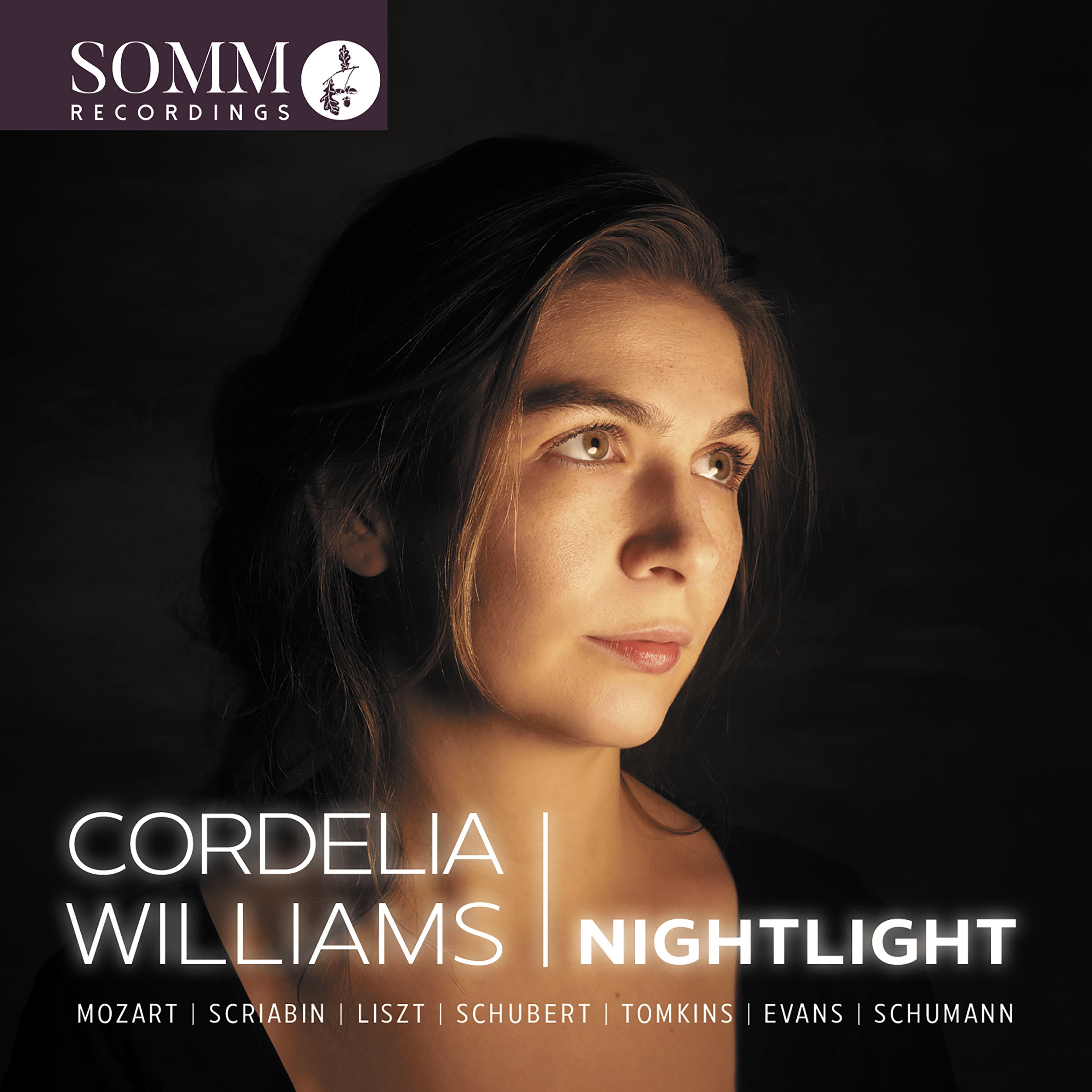

Nightlight

Cordelia Williams studied Theology & Religious Studies at Clare in 2006. In that year she was a named Piano Winner in the BBC’s Young Musician of the Year competition, and since then has performed globally as a concert pianist. Her fourth and most recent album, Nightlight, was awarded Critic’s Choice by International Piano and Recording of the Year by MusicWeb International.

Your recent recording, Nightlight, has been described by Gramophone as “exquisite” and “deeply poetic”. Could you tell us a little about the process of making it?

The idea for the recording formed itself during the countless hazy hours I spent awake with two newborn sons. The music, in various ways, reaches out a hand of consolation or recognition in a time of need. I felt that night-time somehow symbolised a desperation and loneliness - but at the same time a feeling of peace, solitude and hope. The title Nightlight represents that contradiction of new parenthood: uncertainty and self-doubt, endless frustrating nights responsible for a tiny human, yet equally an abundance of love and excitement. I wanted to put the recording together like a journey or progression, so all the key relationships and musical motifs lead us from one piece to the next. Every piece throws new angles on its companions, giving new light in which to understand some well-known music.

Nightlight, recorded in December 2020, was to be my fourth album for SOMM; thank goodness recordings could still go ahead during the pandemic (one room for me and the piano, one room for the producer and engineer) because having that to practise and prepare for kept me sane with concerts cancelled. The concept of comfort during the darkness and hope within desperation turned out to be very prescient when my husband and I came down with COVID two weeks before the booked recording sessions. Being horribly ill and in quarantine with two children wasn’t exactly the calm fortnight of final preparation I had envisaged. But in the end I think the intense emotional and physical struggle of those two weeks added something to the poignancy and depth of the album, as I came out of isolation

the day before the first recording session.

Is there a piece from Nightlight which is particularly meaningful to you? If so, why?

I think my favourite surprise on the album is Thomas Tomkins’ Sad Pavan for These Distracted Times (I was inspired in this choice by my mother, a harpsichordist) - it leads so perfectly into Bill Evans’ jazz masterpiece, Peace Piece. The composers are writing three centuries apart but somehow the musical languages seem to speak to one another. Moments like this, when things just click into place, are why I love programming. In a personal sense, the Schumann Songs of Dawn helped me out of a period of darkness and doubt in myself with their shimmering beauty and hope for an approaching dawn, so they will always be close to my heart.

You recently spent six months in Kenya working with aspiring young pianists. What did you learn while you were there?

Mostly, it was just exciting and inspiring to see the drive and determination of some immensely promising, and largely self-taught, Kenyan musicians. Working in depth with pianists like Teddy and Benaars is one of the most rewarding things I’ve done, I think, because the strength of their desire to improve was so refreshing and invigorating. They went out of their way to learn as much as possible from me and visibly devoted their complete attention and energy to absorbing the new ideas I presented them with. It is such a pleasure to work with someone like this, and that humility in the face of music’s depth is something I hope to always maintain in my own career.

I am now planning to visit Nairobi two or three times per year to carry on coaching and mentoring the most promising pianists I found; I can’t wait to see how they continue to develop with a bit of consistent investment in their talents. I also hope that I will be able to find summer school places for some of them. By common consent among those I spoke to in Kenya, just one or two weeks of focused music-making and learning, as well as meeting other serious young musicians, can be a life- changing opportunity.

I also learnt a lot myself, in the totally new and surprising direction of film-making and editing! Working with a Kenyan cameraman and with support from the Royal Philharmonic Society’s Enterprise Fund, I spent time getting to know some of the musicians I met and coached, hearing about the obstacles they face in trying to learn classical music. The resulting documentary film, On Being a Pianist in Kenya, is one of my proudest and most unexpected achievements.

"I’m most inspired by people combining diverse ideas in new ways, making new meaning and insight from apparently disparate elements.”

Who inspires you?

Hmm, good question - so many things! There are certain pianists whom I greatly admire - Dinu Lipatti, Richard Goode, Grigory Sokolov, Radu Lupu - who, at their best, seem to become a conduit for the music. There’s no ego or effort that gets in the way, just the music speaking in a way that is completely natural, connecting with some fundamental human truth. I do aspire to this level of unity with the music I play.

In terms of my own projects and creativity, I’m most inspired by people combining diverse ideas in new ways, making new meaning and insight from apparently disparate elements. For example, Michael Symmons Roberts wrote a sequence of poems for one of my projects, presenting the story of Christ’s birth and death in the context of 1940s war-torn Paris. The result was unexpected and very moving. Much of what excites me creatively comes back to the world’s religions, people’s deepest beliefs and what it is to be human.

Take us through the daily life of a pianist.

Well, my daily life is currently extremely variable depending on the day of the week, due to my two young boys. In the years B.C. (before children) I would spend usually 4-6 hours a day at the piano, six or seven days a week. The rest of the day would be spent mulling over the music I was working on, slowly processing the meaning of any passages I was having trouble understanding, walking, stretching my arm, shoulder and back muscles, and thinking about concert programmes and future project ideas. That kind of planning always takes a lot of research, listening and reading. I’d also spend one or two hours emailing with venues, promoters or collaborators. On a concert day my routine is completely different, with travelling, rehearsing, calm focusing and resting - no emails!

Now that I’m spending 4 days of the week caring for my children, everything is obviously a lot more compressed. I sometimes practise during their nap times, at weekends and in the evenings when they’re in bed, but generally all my work is condensed into three very full-on days. I do really struggle with not having enough ‘mulling over’ time or the space to slowly think and make decisions. The music I’m working on is always there just below the surface and I have to make a conscious effort to shut it out and be fully present with my children. I’m gradually getting better at compartmentalising: some days I’m only a musician, and some days I’m only a mother. I try not to attempt both at once. Sometimes multi-tasking ends up being less effective and satisfying in the long run!

Cordelia’s recordings are available to buy or stream, her videos can be found at:

youtube. com/CordeliaWilliams

Her book, The Happy Music Play Book, was published last year.