"As a scientist, my job is to embrace uncertainty..."

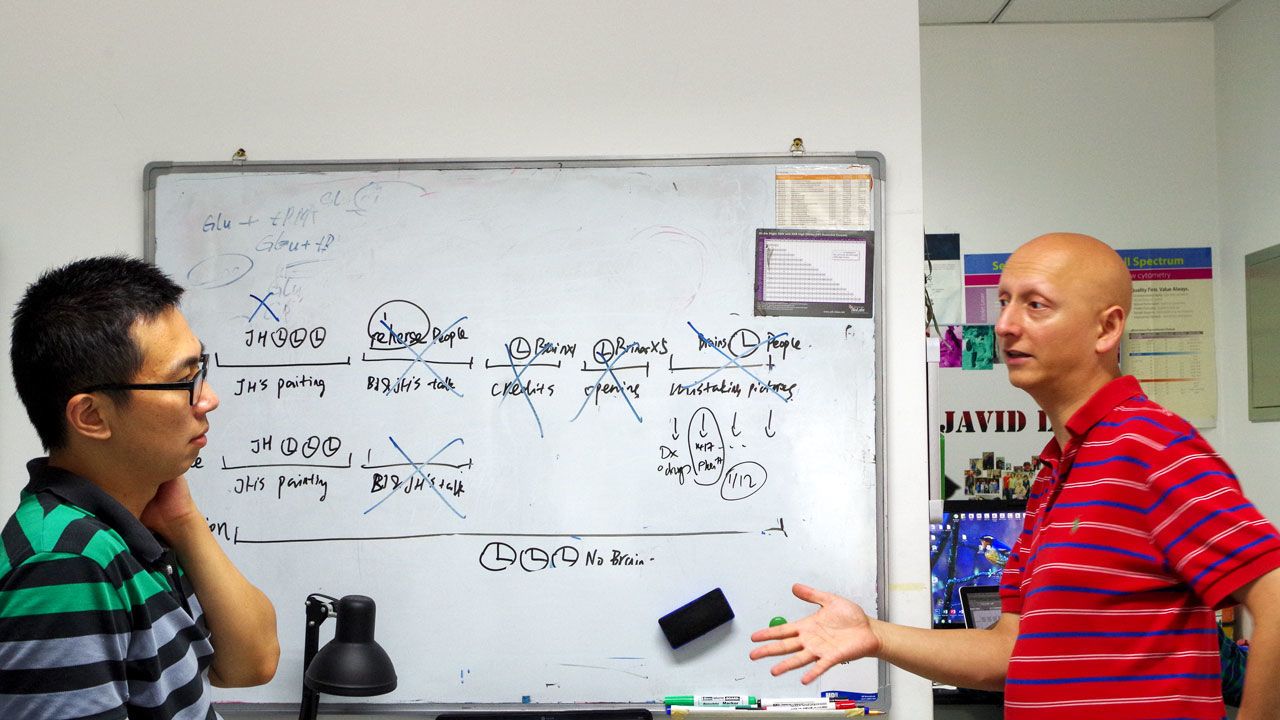

Professor Babak Javid (2002)

Babak Javid (2002), who gained his PhD in Molecular Immunopathology from Clare, is a Professor at the Tsinghua University School of Medicine in Beijing, a Visiting Senior Research Fellow at University of Cambridge Department of Medicine, and a consultant in infectious diseases at Cambridge University Hospitals. He is also a former Fellow of Clare. Here, he gives his personal perspective on COVID-19.

I first heard about what is now known as COVID-19 on 5th January on my way to China Central Television headquarters in Beijing for a pre-arranged live interview on their flagship (English language) news programme to talk about the biggest health news story of the day –domestic production of a difficult-to-manufacture vaccine. The producer texted me to ask if it was OK to have one ‘add-on’ question about ‘Wuhan pneumonia’. I Googled the term – although the WHO had been informed by the Chinese government on the last day of 2019, it hadn’t made it to the news or my radar. Both Chinese authorities and the WHO insisted “there was no evidence” of human to human transmission. In the interview I said it was very early to say, but if there was no human to human transmission, there was nothing to worry about; but the next 10 days would be critical, and openness and transparency were key to dealing with the situation.

Within three weeks, whilst I was in a meeting in Switzerland, it was clear that containment had failed, and that we were facing a global pandemic of unknown severity – the most serious in a century – but I had no inkling how variable the outcome of COVID-19 would be in different nations: in part due to the political response, but also due to still as yet poorly understood biological variables.

COVID-19 also interfered with my own life in ways I would not have conceived. After eight and a half years in Beijing, I had decided to take up a position at the University of California, San Francisco. My prolonged visa application had just been completed, and I was due to hand back my passport to the US Embassy after my Switzerland trip: but I never made it back to Beijing. My return flight was cancelled, and the US Embassy in China shut down and stopped processing visas. I found myself in the UK, staying with my independent but elderly mother. I managed to get my family (US citizens) out to the US to stay with my wife’s family. We spent the next 5 months separated until I was finally issued my visa from the London US Embassy.

Separated from family, my Beijing students, and my new American lab, I took the opportunity to learn as much as possible about this new disease. It soon (in February) became clear that unlike SARS, where patients only transmitted infection several days after becoming severely ill, the maximum ‘viral load’ of COVID-19 patients was just before or at the onset of symptoms and therefore I felt global spread of the new infection was inevitable.

But it also suggested that wearing masks could reduce emission of virus-borne particles from individuals – who wouldn’t even know they are infected – and thus reduce transmission, and even afford some protection to the uninfected wearer.

This idea of ‘universal masking’ didn’t seem radical to me – it had already been adopted in China and most East Asian countries – but we now had a firm scientific rationale for doing so.

However, speaking with colleagues in the UK and the US, I was astounded by the level of professional resistance to the idea. A few colleagues did rally and together we reached out to as many influential scientists, politicians, journalists and thought leaders as we could – with almost no success. Frustrated, we tried to publish our perspective in a medical journal: but that also met with fierce resistance. The British Medical Journal finally agreed to publish, but only after many weeks of to-ing and fro-ing.

The mask issue taught me several lessons. In part, the response to COVID-19 has been characterised by hubris. Masks are a cheap and old technology – and, if we're honest, we still don’t know precisely how effective universal masking is. That slight uncertainty, characterised again and again by the phrase 'no evidence of' impeded our willingness to implement interventions that, in retrospect, seem obvious. More surprisingly, faced with an emergency and uncertainty, we seemed unwilling to even generate the necessary ‘high quality’ evidence. We seem less averse in adopting expensive solutions. After mantras of ‘no evidence of’ aerosol transmission for months, acknowledging that COVID-19 can be transmitted by aerosols (although it’s still unclear what that may mean in terms of longer-range transmission, e.g. in a shared large room), some want to retrofit all buildings with HEPA filters, even though we don’t know how effective such an intervention would be, and again unwilling to investigate that uncertainty by doing the necessary studies.

As a scientist, my job is actually to embrace uncertainty. Science and our understanding of the evidence is not static. I don’t envy leaders – they need to make difficult choices without clear and defining evidence much of the time – but both scientists and leaders are increasingly reluctant to admit that there are still genuine unknowns about this disease (and many other diseases!). As a society, we need to give room for our leaders to change their minds, without it becoming a ‘gotcha’ moment. I have changed my mind countless times in the last 10 months, and I consider that a sign of strength.

If we punish our leaders for doing the same, they may be more rather than less reluctant to make bold decisions.

We still have many questions about COVID-19: why have resource-limited countries in Africa and much of Asia been relatively spared; what will an ‘effective’ vaccine look like, and what will its impact on morbidity, not just infections and mortality be; and many, many others. However, as a scientist, I have also been astounded by the superb global scientific response to COVID-19. The UK has been the world leader – bar none – for clinical intervention trials. As a global community we have made many astonishingly rapid scientific insights into a brand-new disease. Yes, COVID-19 is the most serious pandemic in a century.

But it is not an existential threat. Humanity will inevitably emerge from its shadow, but we can also decide whether we will learn the lessons that this extraordinary chapter in our collective experience can offer us.