Professor Roel Sterckx

The Importance of Chinese History and Culture

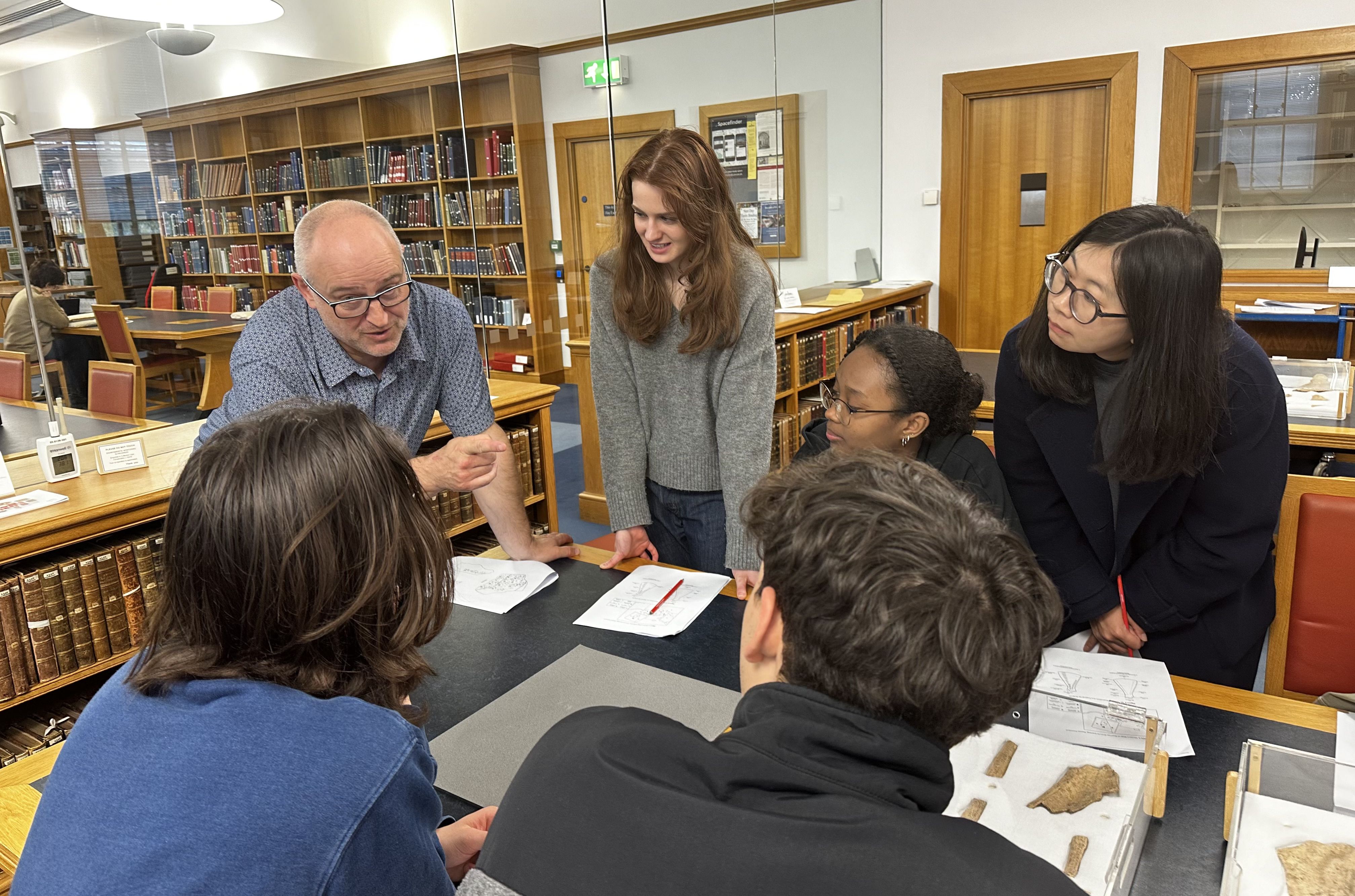

Clare Fellow, Roel Sterckx is a sinologist. He holds the Joseph Needham Professorship of Chinese History, Science and Civilisation in the Faculty of Asian and Middle Eastern Studies and joined Clare in 2006. He was elected Fellow of the British Academy in 2013. In 2018 Roel was awarded a Distinguished Alumni medal by the Taiwanese Ministry of Education for services to Chinese Studies. Clare Review invited Roel to share more about his work, offering insights into his research and contributions to the understanding of Chinese history and culture.

I study China and Chinese civilisation. My focus has been China’s classical age, a period roughly stretching from the ninth century BCE up to the foundation of the Chinese empire by the First Emperor, Qin Shihuangdi, in 221 BCE and the succeeding Han dynasty. This was a time when China gradually evolved from a confederacy of feudal states into a unified empire, a shape it retained until 1911. It is known as China’s “classical” age, because scholars who first studied China compared this period’s influence on Chinese civilisation to that of the Greco-Roman period in the history of Western civilisation.

During this period a canon of texts came together that would directly, or indirectly, shape the thinking of every person of influence in China for centuries to come. It witnessed the development of Chinese historiography and the growth of administrative record keeping. This was also the time when China produced some of its greatest philosophers, including its most influential figure, Confucius (551-479 BCE), whose statue is perched next to the Fellows’ Garden overlooking the Avenue.

I work mostly with primary sources composed in classical and literary Chinese. Alongside publications in European languages, most scholarship in my field is published in modern Mandarin and Japanese. Chinese writing has a continuous history of more than three thousand years. Until the early twentieth century, classical Chinese was the main language of official written communication across East Asia. Its reach can be compared to that of Latin and French during large parts of European history or perhaps even English today.

In addition to texts that have been transmitted through the ages (so-called received texts) and material evidence gathered by archaeologists, we also work with an ever-growing body of newly excavated texts. Rapid modernisation and construction activity has meant that China has been the scene of unprecedented manuscript finds in recent decades. Previously unknown texts written on thousands of bamboo slips, wooden slats, and silk have been unearthed in recent decades. Many were buried in tombs. Work on these new sources (some of which remain unprovenanced or have been acquired from the black market) requires an army of philologists and paleographers.

These manuscripts are reshaping our understanding of early Chinese society and fill in major gaps in traditionally transmitted sources.

Within this corpus of received and newly excavated sources, one of my main interests has been understanding traditional Chinese attitudes towards the natural world and its resources. One of the best ways to understand human societies is to examine how humans handle the non-human world. Hence, I study Chinese attitudes towards the animal world, plants, food and agriculture. I explore how views of the natural world percolate the world of ideas.

At times this leads me to work on topics I never thought I would write about. For example, during the pandemic I researched early Chinese attitudes towards “excrement”, that is human and animal waste, including how human nightsoil was used as fertilizer. It struck me how, despite a wealth of evidence present in texts and archaeology, hardly any scholar had written about it. Yet one can argue that for the majority of early China’s peasant population, the economics of the latrine and the household pig were much more vital than the lofty world of Confucian philosophy! I have just completed a study and annotated translation of two of China’s only remaining treatises on fish farming and pond construction. I hope to find time next to turn to a hitherto unknown manuscript on veterinary medicine, mostly dealing with the horse.

Ironically, the study of the ecology of traditional Chinese society, its attitudes towards natural resources and the environment has never been more relevant than today. Yet in a world in which educators, policy makers and the media tend to orientate their interest, or disinterest, towards China based on short-term contemporary political cycles, we tend to overlook that studying China’s deep past is essential to our conversations about today’s China. At Cambridge we do things differently. Both our research and teaching are grounded on the principle that one simply cannot understand China today without having been exposed to its rich and copiously documented past. The fact that the average Chinese student and young professional today is much more knowledgeable about “the West” than we are about China should ring alarm bells.

Unless we integrate the teaching of Chinese history and culture into our regular school and university curricula, we are bound to lose in a race for knowledge and knowledge-transfer that will prove vital for the current and future generation.