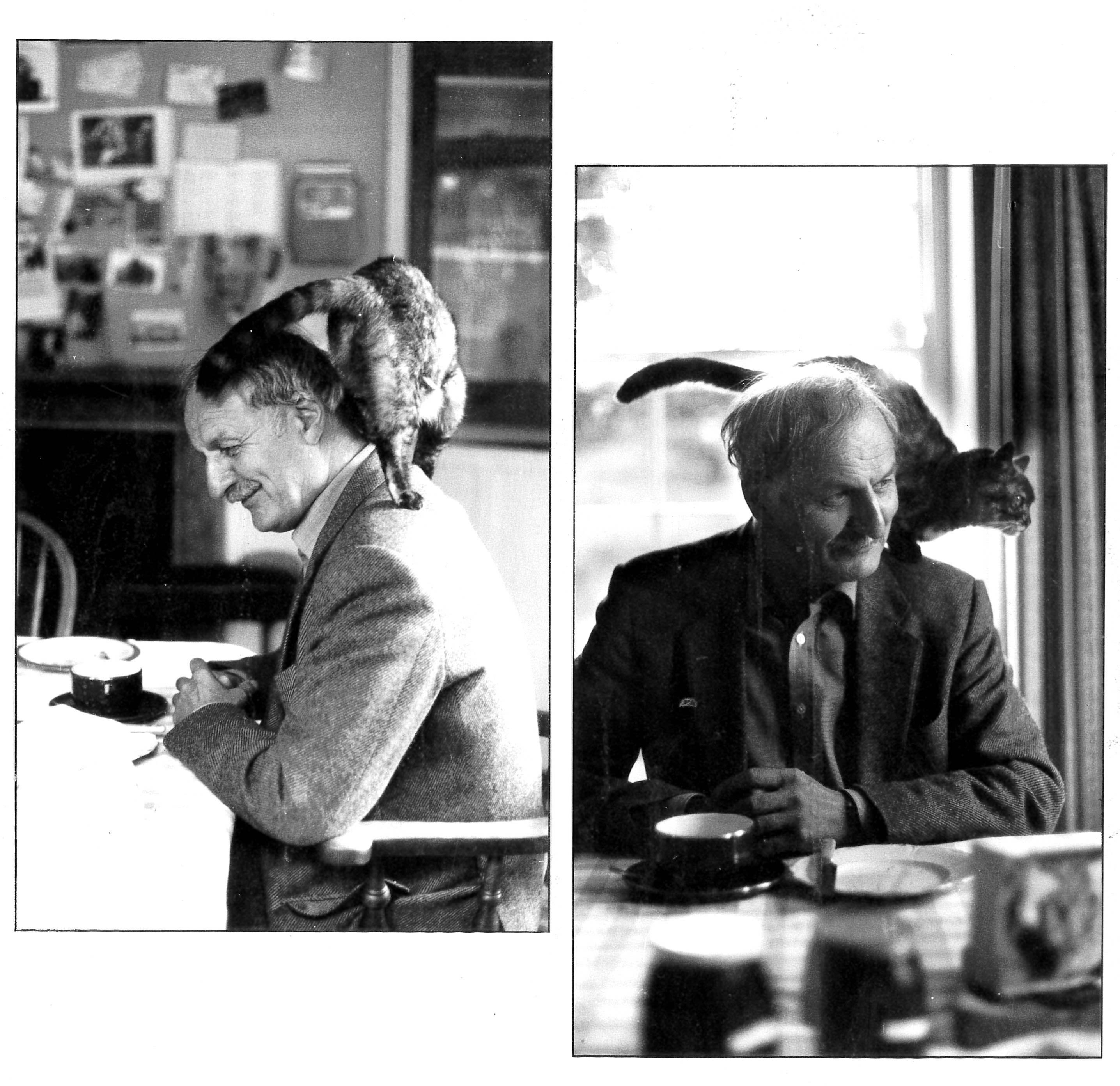

Remembering

Charles Parkin

Charles Parkin came to Clare as a Research Fellow in 1955 and remained a member of the Governing Body until his death in 1986. In Clare Through the Twentieth Century, published to mark the new millennium, Polly O’Hanlon (1972, Bye Fellow, Former Fellow and Senior Tutor) wrote:

‘Charles was special: a long-standing resident Fellow who brought his qualities of quiet understanding, patience and humour to his teaching, and whose supervisions often merged into an extended rumination on the nature of history and its limitless possibilities… It was from Charles, too, that students in the College often learned something about Clare as a community… Community here meant rather a vigorous and often critical companionship between people who lived as well as worked together, for whom the dynamics of intellectual exchange, friendship and criticism provided an environment at once stimulating and nurturing.’

More recently, Professor Jonathan Lear has added his own reminiscences:

‘Charles Parkin was a modest man, somewhat self-effacing. He was a bachelor living in college rooms, and his life was given over to grasping the world in its entirety and in all its beauty. To enter Charles’s rooms at Clare was to enter a certain kind of wonderland. The rooms were lined with books spanning historical periods and geographies and all of Western philosophy. He also had a precision microscope, along with a current sample of pond-water and sketches of micro-organisms that were at various stages of completion. Charles had a fine telescope, and students were invited over in the evening to look at a constellation or a planet that had come into view. This Renaissance-man was a history don at Clare. He was the soul of the College in that generation.

Charles had an extraordinary collection of records, vinyl LPs, and of an evening, with the lights dimmed we would listen. One of my favourites was a recording of trains pulling out of various railway stations. We could hear the Orient Express leaving Vienna or the trans- Siberian railway chugging along to somewhere. On another evening we listened to a BBC recording of approximately 50 different British accents. Charles took me on a tour of Great Britain via the different sounds people made as they tried to make themselves understood. One can think of the wandering states of mind developed on such evenings as ‘dreaminess’, but I have come to think of it as a different form of attunement to different aspects of reality.

At the end of World War II, Charles took his bicycle and cycled all through war-devastated Europe. Somewhere along the way he contracted tuberculosis and ended up at a sanatorium at the old Royal Papworth Hospital, about ten miles west of Cambridge. In that period of recuperation, Charles had an epiphany in which he grasped the whole, intuited the unity of subject and object. The rest of his life, Charles once told me, was a ‘vain attempt to recapture that moment’. Here is a thread of wistfulness that ran through the fabric of a loving, enquiring and basically happy life.’*

* Extracted from a tribute to the late Professor Jonathan Spence (1956) delivered in Battell Chapel, Yale University, on 22 October 2022. The Editor is very grateful to Professor Lear for permission to reproduce his words in Clare News.