Clare College Choir in Venice:

or, Our part in the ending of the Cold War

I can’t honestly remember who thought of the idea, John Hall or I. He was the urbane and worldly founder-director of a very successful pre-university course in Venice, focussing mainly on the arts, which runs under his son’s guidance to this day. We were sitting over dinner in Severino’s, his favourite Venetian eating-place and after-hours hangout, with the talk flowing as freely as the vino tipico.

The year was 1977, and I was the young, eager but woefully inexperienced Director of Music at Clare College; John had impulsively invited me to lecture at his pre-university course. My lectures, to which I had grandly given the ridiculously all-encompassing title Music: Past, Present, Future were, as I recall, a half-baked lasagne of nebulous ideas on the nature of musical language and communication – probably soon forgotten by their polite audience of students scarcely younger than I was, and certainly best forgotten. But as John and I talked, an idea was born: how about bringing Clare Chapel Choir to Venice, to sing Venetian music in the buildings for which it was written?

Nothing might have come of it if several lucky stars had not been shining that night. First, I should freely admit that I had fallen in love with Venice – the most worthwhile fruit of my lecture visit – though this had happened for perhaps unusual reasons. As a musician, my first reaction on entering a church or other historic building is generally not to marvel at the art and architecture but to assess its potential as a venue for music-making. I clap my hands and sing arpeggios to evaluate the acoustics, pace up and down to measure the available performing space, count the audience seats, make a mental note of the state of the heating and lighting . . . and try to make contact with the ghosts. Who made music here in the past? What sort of music? How might it have sounded? What sort of music would sound best here now?

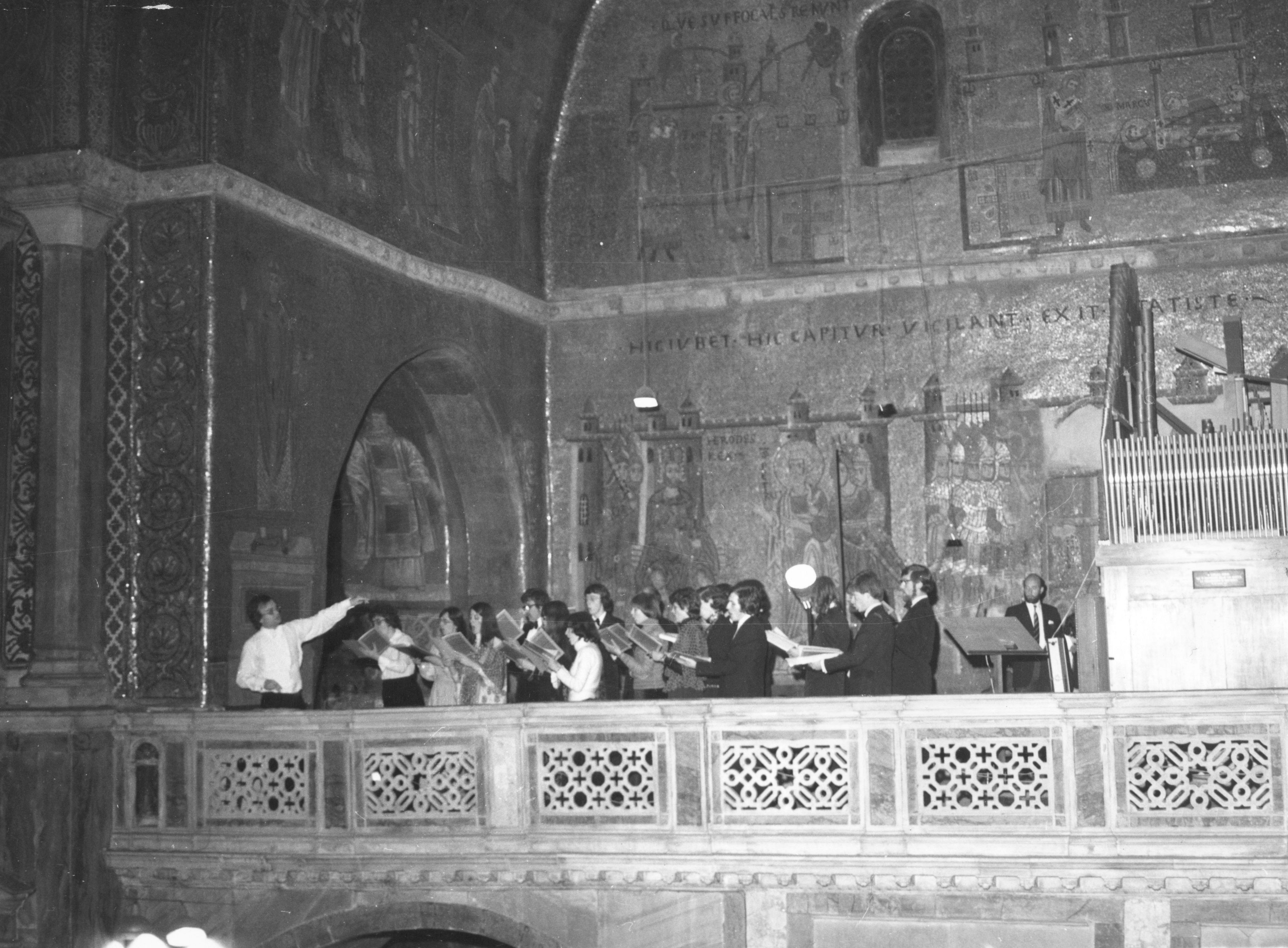

My generously light lecture schedule had left me ample time for this reconnaissance work, and it was obvious that Venice was filled with wonderful venues crying out for music, many of them often silent except for the chatter of tourists. In the Renaissance and Baroque era great musicians lived and worked in Venice – the Gabrielis, Monteverdi, Cavalli, Vivaldi – and fine music was regularly heard in basilica, church, palazzo and scuola. It came as a shock to me, looking around the choir gallery in S. Marco where once Monteverdi had stood, to find that the only sign of music-making was an electric guitar left in the corner, a chord chart on its music stand.

So far, so lucky: I was already fired with a grandiose mission to fill Venice once more with choral singing, repatriating its musical heritage. It also so happened that in Cambridge a momentous change had recently come about: three brave men’s colleges, mine among them, had started to admit women in 1972, and this had transformed the singing of chapel choirs such as ours at Clare. Boy sopranos recruited locally had long gone – unlike King’s and St John’s we had no choir school to provide boy sopranos – and until the coming of women, Clare Choir was a male-voice group, a pale echo of the Red Army or the miners of Merthyr Tydfil. But now we had women, feisty and up for the challenge of proving their superiority to boy sopranos on an international stage – a mixed chapel choir, after almost 650 years in Clare without one.

Ever practical and diplomatic, John Hall began to pave the way for a visit, opening doors to us. If we were to sing in both sacred and secular venues – not only S. Marco and other glorious churches but the Scuola di S. Rocco and the Conservatory – it would need the co-operation of the Comune di Venezia, the city council, which was Communist, and the Catholic Church, which was, well, Catholic. I am told that in one of Venice’s most select restaurants the head of the Comune and his Catholic opposite number were seen discreetly dining together, finding (according to John’s later account) common ground in their wish to celebrate Vivaldi’s 300th anniversary in 1978 but embarrassed to have no plans in place. What better – and more politically uncontentious – than to bring in a group from somewhere else with a ready-made programme of musical events celebrating Vivaldi and other renowned Venetian composers? Now that Eurocommunism is a spent force, such harmonious collaboration seems unremarkable, but in the Venice of the 1970s it was, apparently, unprecedented. We were to be allowed to perform anywhere we liked.

Both the Communists and the Catholics probably appreciated another point in our favour: we came cheap – unpaid, in fact. But, counting our little orchestra and some extra Cambridge voices recruited to bump up numbers, we had just over fifty mouths to feed during what turned out to be an eight-day visit, and I can still smell the welcome aroma of minestrone and home-made pasta kindly provided after each day’s music-making, courtesy of the Comune, at a pleasant restaurant near La Fenice, after which we took our night’s rest in accommodation similarly provided by the Comune. Who would pay our airfares, though? As impoverished students we could not necessarily pay our own way, so I boldly wrote to the British Council for help. Despite the insufferably wheedling and presumptuous tone of my letter (I have kept a copy), amazingly I received a courteous and positive reply from the British Council music adviser based in Rome, a wonderfully kind, widely cultured man named Jack Buckley. In due course we met in London, and over dinner he delicately suggested to me a quid pro quo: it might be appropriate if we included a proportion of English music in our concerts and church services. No hardship as far as I was concerned: some Tallis, Purcell and Stanford in exchange for our charter flights. I would have been willing to throw in recitations of Shakespeare, Dickens and Wodehouse in the Piazza San Marco.

We were able to time our visit to coincide with Holy Week and Easter, which opened up rich opportunities to contribute to the liturgy of Good Friday and Easter Sunday. On Good Friday we sang at the traditional three-hour Veneration of the Cross in the lovely little church of S. Niccolo dei Mendicoli, then being restored by the Venice in Peril organisation. The aged priest was visibly moved as we, an Anglican choir, sang the appropriate Gregorian chants and polyphonic Good Friday music he had last heard, so he told me afterwards as we sat in the vestry, more than fifty years ago at his Catholic seminary. He opened the church safe and took out an outsize bottle of red wine, wagging a finger as he reminded me that this was the most solemn day of the church’s year. I nodded. But, he went on, in two days Christ would rise again and we should be joyful. He poured two huge glasses of the wine, toasted Clare Choir and we drank.

On Easter Sunday morning it was High Mass at Palladio’s imposing marble Church of the Redentore on the Giudecca, similar in design and scale to Palestrina’s Lateran church in Rome, and as we sang his Missa Papae Marcelli, the soaring polyphony with its high tenor parts made sense to me in a quite new way: marble reflects the tenor voice better than the stone of an English cathedral, a reminder that music generally works best if performed in its intended setting. One more Easter church service remained: Anglican Evensong at the English Church, where we treated the expatriate Brits to a nostalgic warm bath of Stanford canticles and Sir William Harris’s Faire is the heaven (to words by Spenser). The congregation perhaps shed a tear for the old country, but they didn’t seem in any hurry to return there. Eurocommunism had its drawbacks, no doubt, but Jim Callaghan’s Labour government, with pre-Lawson rates of income tax, inflation at over 20% and the Winter of Discontent shortly to come, probably seemed even less tempting.

The church services were only a part of our busy week’s music-making. We also gave four concerts, two in the Scuola di S. Rocco, one in the Ospedaletto, our final one in S. Marco, where, exceptionally, we were allowed an evening rehearsal with a free run of all the various galleries so we could experiment to find the optimum layout for all the antiphonal music so strongly associated with the building. Fashionable Venice turned out in force for us at every event. The left-leaning Comune officials, including the noted avant-garde composer Luigi Nono – surrounded by well-built minders in dark glasses – seemed more in evidence at the Scuola concerts, Catholic dignitaries were to the fore at the church concerts, but both were definitely present, with Jack Buckley, representing the British Council, loyally supporting us in the front row throughout. The music we performed ran the gamut of Venetian repertoire: Gabrieli motets in S. Marco, Monteverdi (lots of him), Vivaldi concertos and the inevitable Gloria, twiddly organ pieces by lesser lights of the early Baroque, and, as our finale in the S. Marco concert, the Messa Concertata by Cavalli, Monteverdi’s successor as maestro di cappella at S. Marco. In deference to the British Council we also sang plenty of English music in one concert or another, including Tallis’s great 40-part motet, first indoors in the Scuola di S. Rocco and the next day in the Piazza S. Marco to a probably bewildered audience of tourists. Don’t try this, by the way, it doesn’t really work outdoors.

Taken in the Basilica of San Marco, Venice, on Easter Monday 1978. They show Clare Choir in two halves, singing from opposite galleries at the east end of the basilica. The white-shirted figure with outstretched arm on the left of the second photo is me.

The S. Marco concert was graced by the presence in the front row of the Patriarch of Venice, soon to become Pope John Paul I. At the end of the concert he embraced me warmly, called me ‘caro maestro’, and when he was elected Pope in September of that year, I was ready to brag to the world about how I had been embraced by the Pope . . . until, thirty-three days later, he died in mysterious circumstances. Conspiracy theorists were quick to blame the dark forces believed by some to be endemic in Italian religious and political institutions, but I prefer to remember another facet of Italy: its ability to lay such things aside and extend a familial welcome to, in our case, an innocent group of student musicians who, by the end of their visit, all truly loved the music, the culture and the people of Italy and would always hold a special place in their hearts for Venice.

There was a charming postscript to our visit. Shortly after our return to Cambridge Robin Matthews, Master of Clare, received a letter from Ray Jacques, British Consul in Venice, which I quote in full:

Dear Master,

I feel I must write and let you know what a great success the visit of the Clare College choir to Venice has been. Not only were they a very hardworking group who set a high musical standard but they comported themselves in a manner that did credit to Britain, to Clare and to themselves. They gave us some lovely concerts, they made the English Church bloom as it can never have bloomed before and they looked good, with their combination of youth and competence. I was very proud of them, and their visit has undoubtedly been a tour de force.

For all this we have many to thank, and to you and all at Clare who made the visit possible I extend the warm appreciation of all of us here in Venice. I would also like to add a particular word of gratitude for the tremendous part that John Rutter played, both in structuring the visit and in holding it all together with so much charm, tact and efficiency.

Yours sincerely, R. J. Jacques H M Consul

Lovely to recall that, in the world of Her Majesty’s diplomatic service, people in 1978 still ‘comported’ themselves. Clare Choir has made many visits to different countries since then, but I believe this may have been the first major one, and I look back on it fondly as a milestone in the history of music at Clare.