Chronicling

the History of Science

Dr Patricia Fara is an award-winning historian of science and a Fellow of Clare.

You were recently awarded the Abraham Pais Prize for the History of Physics by the APS and AIP. What does that recognition mean to you?

When the email came, I was so stunned that I almost deleted it as spam – I hesitated for a whole day before opening the attachments. I still have no idea who nominated me, but I am enormously proud and grateful to be chosen for this great international honour. The full citation reads:

For outstanding and wide-ranging scholarship on the history of science, especially regarding the physical sciences in the 17th through the 20th centuries, and for bringing attention to neglected contributors to the physical sciences, including female physicists and practical workers such as navigators and instrument makers.

I was already 40 when I became a postgraduate, so I hope that this award will encourage other academics to recognise that mature students can – like those ‘neglected contributors to the physical sciences’ – have an important role to play. I also feel that this is a tribute to the countless people who have advised and supported me over the years, especially my PhD supervisor, Jim Secord.

You gave a lecture to the Society on 17th March.

What did you discuss?

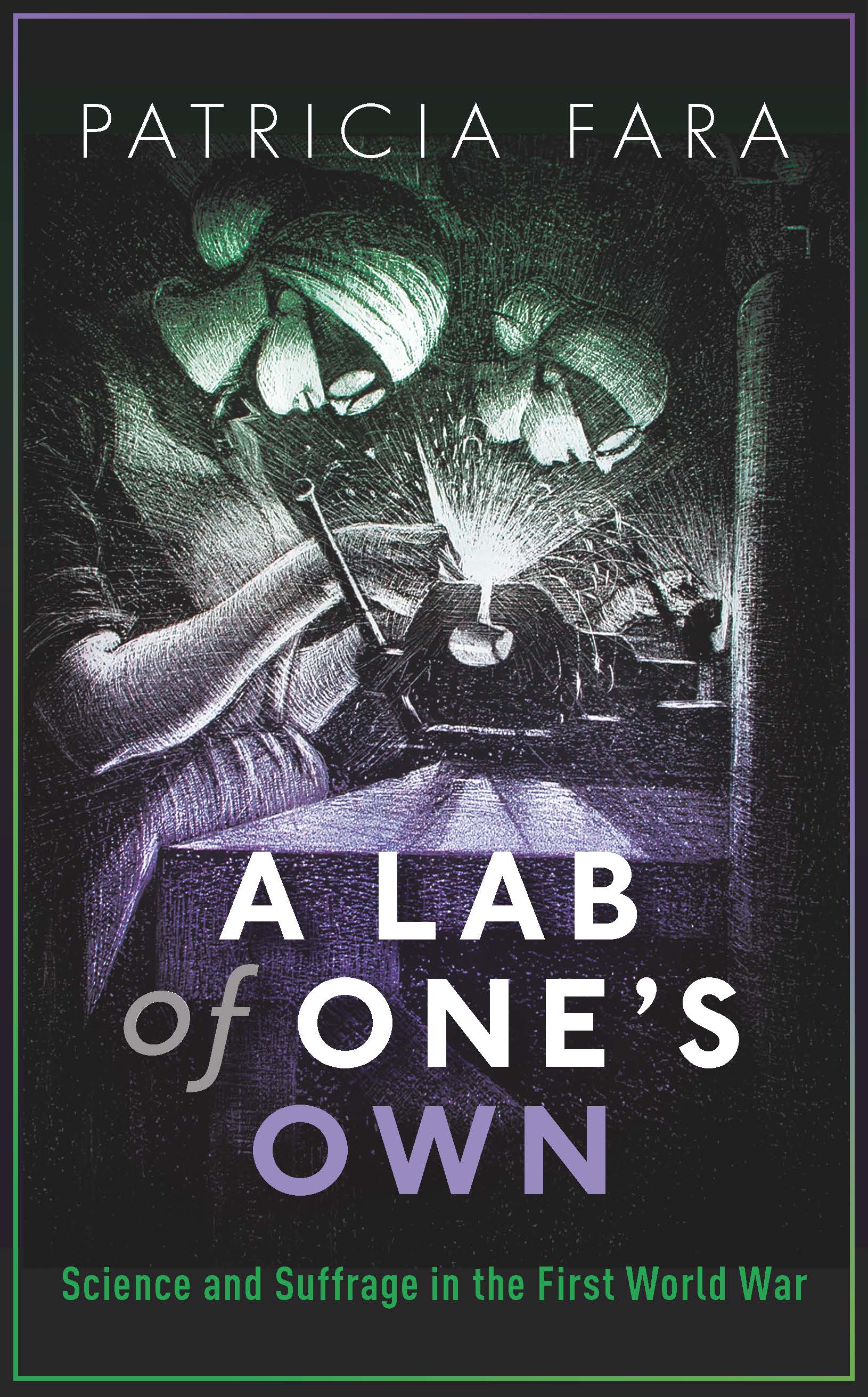

When I was Senior Tutor of Clare, I deliberately wove together three aspects of my life: first-hand experience of being a woman studying physics at Oxford in the 1960s; growing academic interest in female scientists of the past; and current efforts to understand why some scientific courses attract relatively low numbers of female applicants and why there are still so few women at the very top levels of science. As a historian, my aim became to investigate the past in order to understand how we have reached the present – and the main point of doing that is to improve the future. I discussed the achievements of three Cambridge graduates: Marie Skłodowska Curie’s close friend, Hertha Ayrton, who was a distinguished electrical engineer; the medical physicist Edith Stoney, who worked in France and Serbia during the First World War; and one of Britain’s most influential suffrage leaders, the mathematician Ray Strachey.

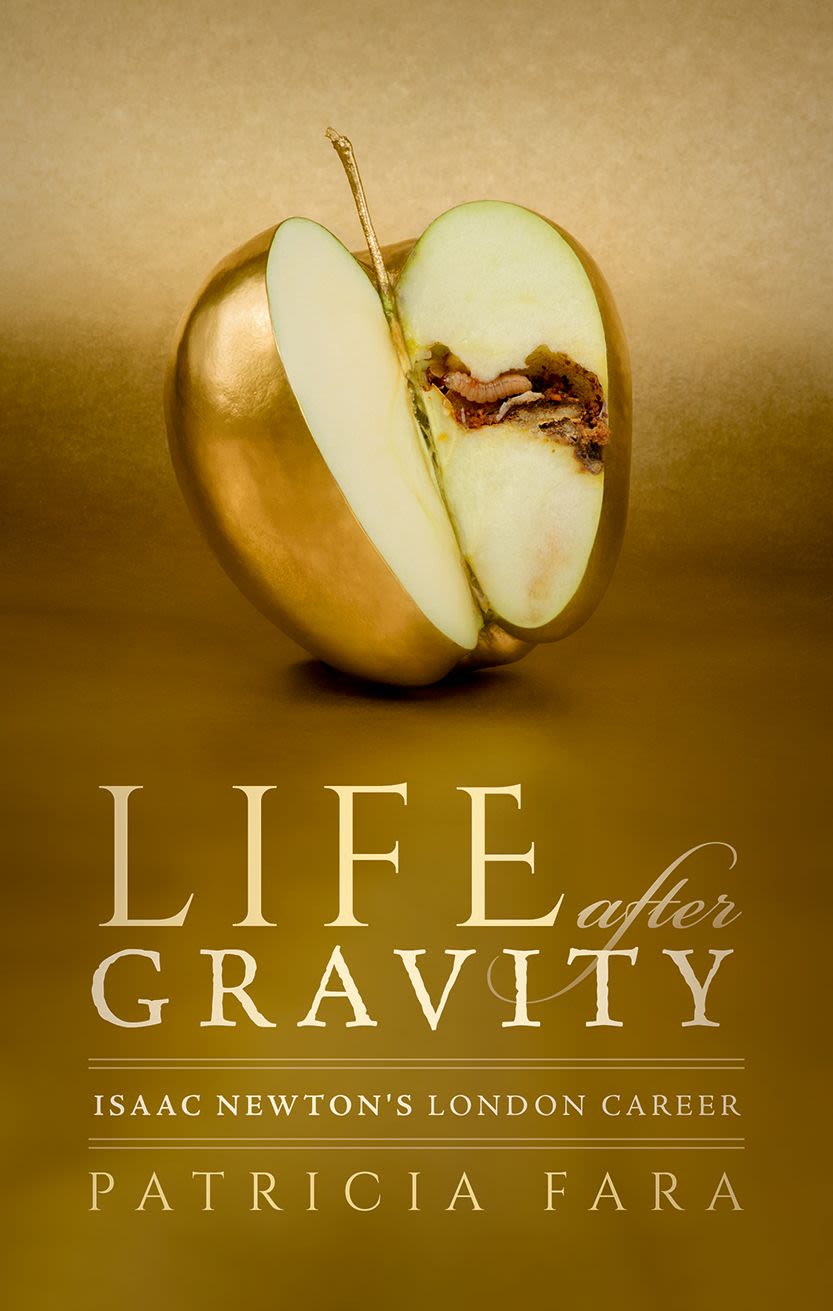

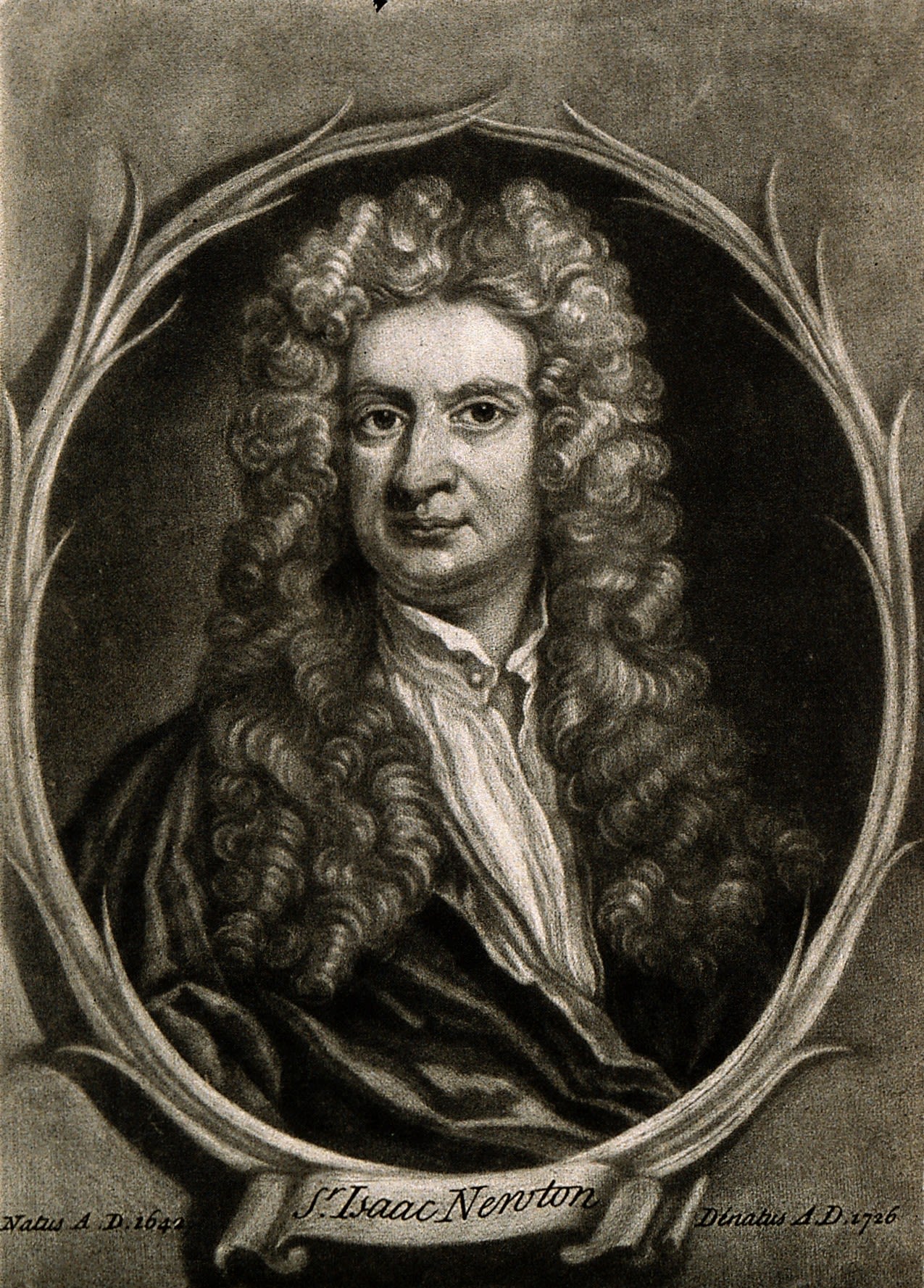

When researching for your most recent work on Isaac Newton’s London career, what discovery surprised you the most?

According to the mythology, Newton was uninterested in worldly possessions and loathed entertaining. I knew that was untrue, but I hadn’t realised quite how rich and sociable he was. When he died, the inventory of his possessions covered seventeen feet of vellum and included twenty pans, two fish kettles, over a hundred drinking glasses and forty plates of best china with another fifty in the kitchen – to say nothing of that ultimate in Georgian luxury, two silver chamber pots.

Newton has become notorious for savaging his rivals, but I had failed to appreciate fully that he was a skilled negotiator who operated by securing the support of influential allies. Deeply involved in promoting Britain’s commercial expansion and global domination during the eighteenth century, he endorsed restrictive taxation measures, invested in trading companies based on international slavery, and profited directly from minting coins made of African gold.

I also discovered that even Newton could make mistakes: he lost a fortune in the South Sea Bubble by buying, selling and then buying in again at a higher price shortly before the market collapsed. But perhaps I should have been less surprised than I was to learn how closely the Royal Society cooperated with what was called its ‘Twin Sister’ – the Company of Royal Adventurers Trading into Africa, founded in the same year under Charles II. The 18th century is often celebrated as the age of scientific exploration, but it was also the era of imperial exploitation.

"As a historian, my aim became to investigate the past in order to understand how we have reached the present.”

What areas of research are you excited to dive into in the future?

During lockdown, I was asked to give quite a few talks on women I had never heard of before, which was challenging but exciting. Among them was an extraordinary Quaker scientist, an early environmentalist called Gulielma Lister (1860-1949), who was hailed as ‘The Queen of Slime Moulds.’ I knew nothing about those micro-organisms, but one kind proved to be absolutely fascinating because they have taken artificial intelligence in new directions. Neither plants nor animals nor fungi, these single-celled creatures have 720 genders and can creep around in the search for food, swarming through laboratory mazes to reach a tasty snack as if they had worked out the shortest route. Their

problem-solving strategies are being emulated by computer programmers producing algorithms for projects as diverse as tracking cosmic filaments, mapping delivery networks and optimizing crowd evacuation routes. They are making scientists think again about what it means to think. Lister was the international expert who corresponded with Emperor Hirohito of Japan and was one of the first female fellows admitted to London’s prestigious Linnean Society. Through her, I have discovered several other unsung female scientists who made crucial contributions to knowledge.

How has the study of the history of science changed since you first became an academic?

During the closing decades of the last century, the history of science and medicine shifted from being largely the preserve of practitioners interested in their own origins to becoming a humanities-oriented field open not only to scientists and doctors, but also to sociologists, anthropologists, geographers, philosophers, literary critics, art specialists and others. Science is so deeply embedded in modern society that understanding its rise to dominance entails exploring every aspect of global culture, and grandiose success stories about inevitable progress from Plato to NATO were rewritten as researchers focused closely on specific episodes. My personal goals have included rejecting the concept of a Scientific Revolution, abolishing any reference to the word ‘scientist’ before its invention in the 1830s, and dismissing the notion of individual genius.

As in other academic subjects, fashions come and go in the history of science: considerations of class and gender are now standard rather than exceptional, and there have been shifts towards analysing books as material objects, emphasising the significance of instruments, and retrieving information about ‘invisible assistants’ – those networks of men and women who were essential for both theoretical and practical innovations but have been overlooked in the historical records.

But history never stands still – there are always new facts to find, new interpretations to carve out. Currently, in line with broader political interests, historians of science direct their attention to creating a truly global narrative of the past, rather than one dominated by Anglo-American perspectives. I tried to engage with these contemporary debates not only in Life after Gravity but also in a book I wrote a few years ago about Erasmus Darwin, Charles’s under-rated grandfather. Being a historian of science is not just a scholarly activity: your personal beliefs, personality and attitudes permeate every aspect of your research.