Charming the birds from the trees

What can magic tell us about how animals think? It’s a question which Professor Nicky Clayton FRS, Head of the Comparative Cognition Lab in the Department of Psychology, and her team seek to answer. Working with human and animal subjects, particularly birds, their experiments compare responses to magic effects, allowing unique insights into the blind-spots of perception and attention across species.

or Nicky Clayton, birds and bird behaviour have been a lifelong fascination – according to her mum, she has wanted to understand them since she was just eighteen months old. “I’ve always been captivated by how they move. It’s what led me to become a dancer as well as a scientist, and it was through my interest in dance that I met Professor Clive Wilkins, who is artist-in-residence in the Department of Psychology – we met on the dance floor, in fact! Clive is a professional magician and a member of the Magic Circle in London, as well as being a bona fide artist and writer. We’ve been working together for twelve years now.”

The lab’s recent experiments with Eurasian jays, in which they tested their susceptibility to be misled by a variety of sleight-of-hand movements, has yielded particularly interesting results and was recently featured in a special year-end edition of New Scientist, as well as publications in Science and the Proceedings of the Natural Academy of Sciences.

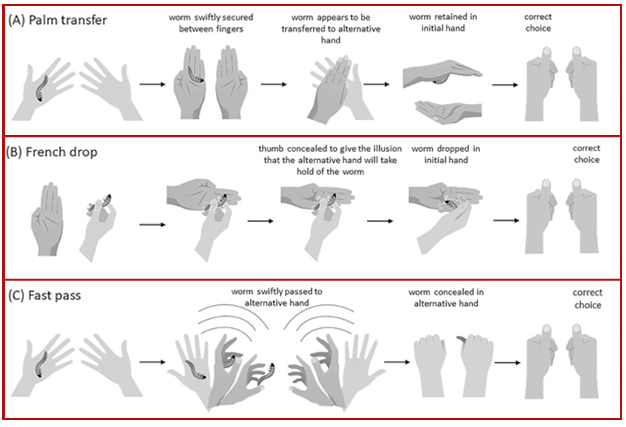

“Humans are not fooled by magic effects because of our linguistic prowess, but because of blind spots in how we see and roadblocks in how we think,” Nicky explains. “We’re fooled by prestidigitation, by the movement of the hands.” In particular, the lab tested three different techniques: palming, the French drop and the fast pass. These movements play with our expectations – through our previous experiences, humans learn that certain hand motions are likely to cause certain outcomes, and the magic happens in the mind of the audience, namely when our expectations are subverted through the magician’s sleight-of-hand. But, the team discovered, while jays could be reliably fooled by some fast-paced movements (those in which the hand acts as a barrier like a wing), they were not taken in by tricks that required opposable thumbs. This suggests that jays, even those hand-reared in close proximity to humans, do not have the same expectations as we do when observing the movement of human hands. For Nicky and her colleagues, their results represent an exciting possibility for further study. “We’re now looking into performing tests on monkeys that have fingers and thumbs of their own,” she says.

It is not only through sleight-of-hand that the Comparative Cognition Lab has been producing impactful work. At the end of 2021, evidence submitted by Nicky and her collaborators resulted in an amendment to the UK Government’s Animal Sentience Bill, after they successfully demonstrated the abilities of cephalopods such as cuttlefish and octopus to remember the past, make future-oriented decisions and exhibit self- control. “The idea that sentience isn’t just about physiology but also about mentality is, I think, a real breakthrough, and it’s great to see that reflected in a government bill.”

So, where will the lab turn its attention next? “I’d like to look at self-consciousness,” says Nicky. “There’s been some very interesting studies done to enquire into whether animals recognise themselves in a mirror, and if so, what that means. But the trouble is, even if animals do show signs of recognition, there can be so many other explanations beyond true self-consciousness: ‘is it really me, or is it someone who looks just like me?’” She points to an example from Disney’s Winnie the Pooh: upon catching sight of himself in the mirror, Tigger (who has just announced to Pooh that ‘I’m the only one!’) suspects an imposter, and attempts to drive his reflection away. In so doing, he frightens himself, and quickly dashes away to hide underneath Pooh’s bed. Nicky and her colleagues are beginning to devise methodologies to explore this question. “I think understanding more about camouflage in cephalopods could reveal some really interesting cognitive abilities about how they see the world and see themselves.”

Nicky’s long history of contributions to the field have recently been doubly recognised by the Association of the Study of Animal Behaviour (ASAB). She is the first person in the society’s history to be awarded two of their foremost honours in the same year, the ASAB Medal and the Tinbergen Lecture Award, with the society citing her vast body of work at the vanguard of research into animal memory and cognition. For Nicky, research has always been about intellectual curiosity. “Still,” she says, “it is nice, especially in recent times when we’ve had so little social interaction, to know that others view your work as important. I’m delighted.”

As Tinbergen Lecturer, Nicky will deliver an address at ASAB’s biannual meeting, discussing the past, present and future of the field of bird behaviour. She is, as she describes it, the ‘great- granddaughter’ of Niko Tinbergen, the pioneering ethologist for whom the prize is named. Her supervisor when undertaking her PhD at the University of St Andrews was Professor Peter Slater, who was supervised by zoologist Aubrey Manning, who was in turn taught by Tinbergen himself. “I’d like to think he would be pleased that I’ve won the award in his name for studying bird behaviour, which he contributed so much to,”

she says.

"The idea that sentience isn’t just about physiology but also about mentality is, I think, a real breakthrough.”

In her address, she will touch upon an idea she believes has perhaps been lost sight of since the era of Tinbergen and his colleagues, who remain the only Nobel Prize-winning scientists in the field. It’s something that has been informed by her passion for dance. “It’s about ‘knowing your animal’. You have to have an understanding that when you do an experiment, you’re creating a two-way interaction. If you get caught up in the numbers, you can miss that: the fact you’re working with living forms of intelligence.”