Cambridge Black

Medics Society

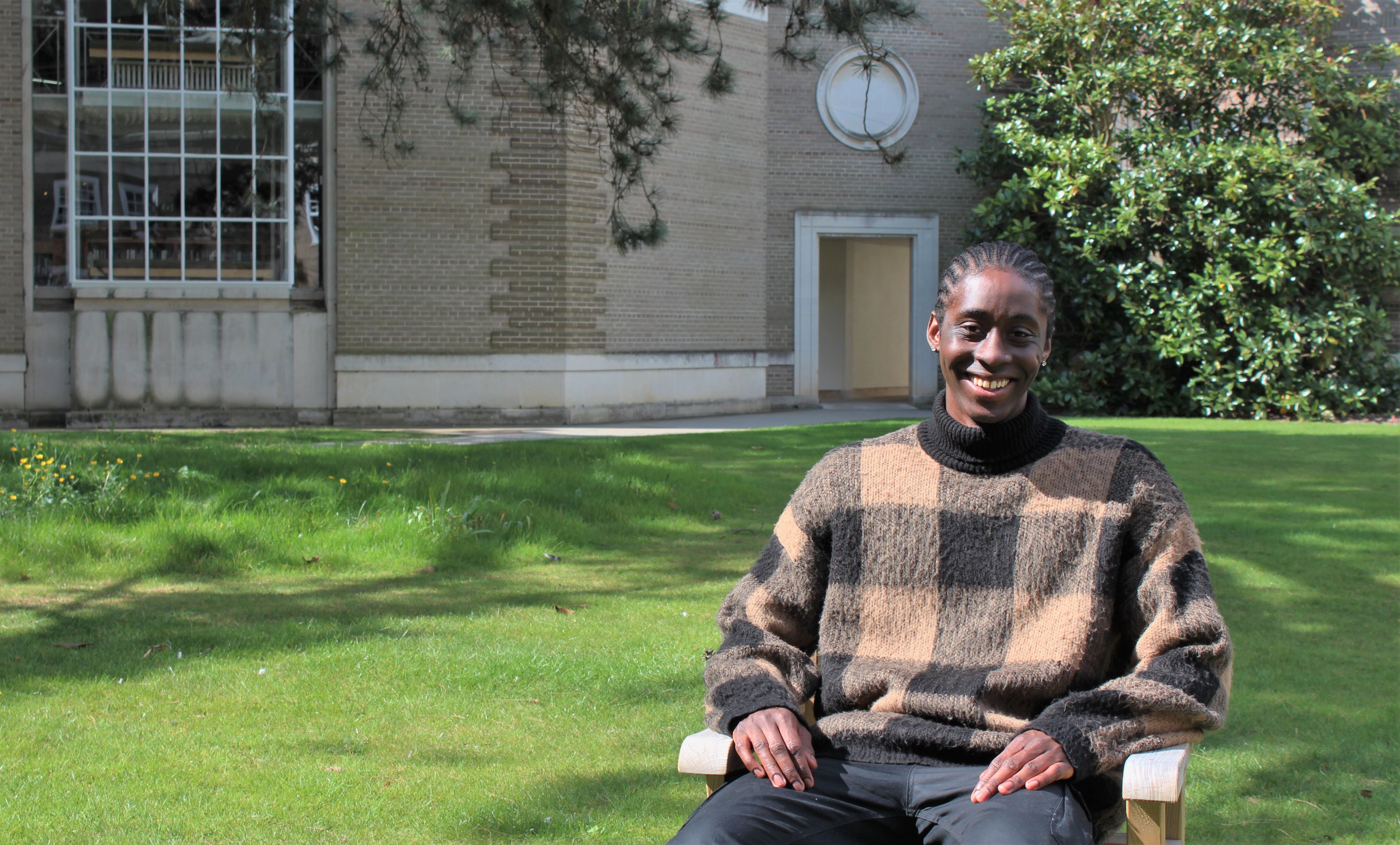

Oliver Moodie (2017) is a fifth-year medical student at Clare. He is the founder and former President of Cambridge Black Medics Society.

The establishment of Cambridge Black Medics Society (CBMS) in the summer of 2020 was the product of both a contemporary social climate and a historic, entrenched need for our existence. There had been several attempts to start a society for Black or ethnic minority medical students in Cambridge before, but none had taken off. So, when Innocent Ogunmwonyi first messaged me in June 2020, saying he thought I should have a crack at it, I was excited by the challenge.

CBMS benefitted from a perfect storm - and there were three major factors, two of which were lemons that we managed to turn into lemonade. Firstly, the deaths of Breonna Taylor, George Floyd and Ahmaud Arbery during the first half of 2020 meant that the Black Lives Matter movement was leading to reckonings all across the globe, and institutions, including Cambridge, were taking a much more critical look at their practices. Secondly, the COVID-19 pandemic was actually a really good time to start a new endeavour.

I knew we wouldn’t have much in the way of funding and the push for digital events via Zoom had provided a cost-effective way of reaching larger audiences and faster than we ever would have been able to in pre-pandemic times. Thirdly, I was just finishing my intercalation in HSPS which taught me how to critically analyse and articulate many of the emotions I was feeling during the events of 2020. It meant I could be so much more persuasive in the ways I talked about my passion for our society by situating our work in the canon of critical race theory and medical sociology. With these factors in play, the next step was setting up our first committee and divvying up roles. Slowly but surely, we were gathering steam.

"The most common response when I said I was setting up a society called Cambridge Black Medics Society was “that’s cool! What is it?”. "

The most common response when I said I was setting up a society called Cambridge Black Medics Society was “that’s cool! What is it?”. Despite having a name that was meant to say what it stood for on the tin, our raison d’être was one of the hardest things to both formulate and explicate. One thing was clear - I had no desire to “boil the ocean” and try to cure racism in the NHS or our society at large. Rather, from the get-go, we were highly focused on how we could be the most effective society for students in our little nook of East Anglia. Despite being a society meant to unify and represent the Black medical students of Cambridge, both present and former, we could not ignore the heterogeneity of backgrounds, motives and desires of the people we were so boldly claiming to represent. So, to discover what needs we could best serve, we decided to survey the Black medical students at Cambridge.

Firstly, we found that 100% of Black medical students at Cambridge surveyed had witnessed or experienced racism in Cambridge, but 0% of students had trust in the current support systems in place. The sheer unanimity of these responses surprised me, but the trends did not. When it comes to welfare, I strongly believe that everyone should be treated equally. Fundamentally, Black students and White students do not face the same difficulties (and 100% those surveyed agree), nor do they have the same welfare needs – so why do we treat them as the same? At Cambridge, many Black students face racial profiling and stereotyping by staff, social alienation and institutional barriers to attainment. We’re also routinely questioned about the validity and accuracy of our experiences of racism, as if they’re fantasies we’ve invented. In our survey, only 14.3% of Black medical students said they would turn to their college or the medical school for welfare support - and I’ve seen students go as far as commuting to London to see therapists who “get it”. When seeing white counsellors or welfare officers, students were often met with a lack of understanding when it came to race. The words “explaining”, “lecturing” and “teaching” came up more than once in students’ testimonials, demonstrating how therapy can quickly slip into providing emotional and educational labour just to get your therapist on the same page as you. Some students found the words and persisted, but some went once and never went back. Overt racism was thankfully rare, but more commonly it was the

little things – being asked “what actually is a microaggression?”, or if you were “really, 100% sure that something was racist”. A one-size-fits-all approach is not the most nuanced way of tackling the student mental health crisis at the best of times and the same groups of people will continue to slip through the cracks if our support services do not respond to the social and political climates that they are inextricably intertwined with. Within support services, people of colour deserve structures created for us, when the wider world is in so many ways structured against us.

Secondly, our survey found issues with teaching in medical schools. In our survey we asked people if they felt Cambridge medical school ‘equips them to be as good a doctor for Black patients as it does for White patients’. 71.5% said no, the rest were unsure. This is a worrying statistic and, despite being a 5th year medical student with only an inkling of life as an NHS clinician, I have experienced this first-hand. When being a simulated patient during teaching sessions, I have to pretend to be White – there are so few protocols, de facto or de jure, on how to manage care for those with darker skin, especially in specialities like dermatology where this is so crucial. In my experience a lack of discussion about race, racism and ethnicity in educational settings often stems from fears of saying the wrong thing, at the wrong time, being “cancelled” or worrying about being inadvertently rude. It’s crazy to me how comfortable medics get talking about poo, strange odours and death, but never get comfortable talking about race. With lay knowledge becoming increasingly important in the medical field, I felt our society could play an important role in improving education, acting as an intercessor to connect the voices of our members to the central faculties and deaneries to enable them to provide better, more inclusive teaching.

Thirdly, we found that it is not enough to just promote diversity in medical schools, because many young Black doctors are falling behind their white counterparts in career progression. Diversity is not enough - we need inclusion. At the moment, across all sectors, minorities entering previously inaccessible fields are experiencing a battle to survive, rather than thrive. The General Medical Council found that mentorship with everyday colleagues is not just important, but instrumental to success in medical school and postgraduate training. Access to supportive supervisors and inspirational senior colleagues is not meritocratic but rather influenced by factors such as gender and ethnicity, making BME learners systematically less able to access them without the interventions designed to overcome barriers. Mentoring is a central component of NHS England’s drive to create, sustain and develop a diverse workforce and we believed that we could play a role in supporting this drive here in Cambridge.

With these themes established from our survey, we ended up creating three ‘veins’ (pardon the pun) to encompass our society’s objectives. Counsel: academic and pastoral guidance for our members who are current medical students at Cambridge; Campaign: promoting Diversity, Inclusion and Equity (DI&E) through curriculum changes within our medical school; Connect: consociate past, current, future and prospective Cambridge medics. We achieved a lot of things I was personally proud of in our maiden year. Presenting at the Faculty Away Day, creating our family system, collaborating with Murray Edwards College, The Sutton Trust, Melanin Medics and Five X More, working very closely with the Dean of the School of Clinical Medicine (Professor Paul Wilkinson) and the Regius Professor of Physic (Professor Patrick Maxwell) and the formation of CBMS Network are just a few highlights in an extremely fruitful year for us. My personal highlight was winning the United Nations Millennium Fellowship which taught me a lot of leadership skills and even let me attend a UN Town Hall Meeting in New York! We are also indebted to Clare College, which has financially supported our endeavours and thus allowed us greatly to expand what we are able to offer in our second year of operation.

"In my experience a lack of discussion about race, racism and ethnicity in educational settings often stems from fears of saying the wrong thing, at the wrong time."

Whilst my committee was very focused on achieving tangible outcomes for our members this year, my number one priority as president was a little more intangible: how could we create something that would last long after I, or anyone else on the committee, was long gone? There was no easy way to solve this but, given that I have now handed over the reins to a new president and committee, I hope we have succeeded - at least for now. The School of Clinical Medicine has been incredibly receptive to changing its curriculum for the better – far beyond anything I could have asked for – and there is a real passion in the School’s deanery for progress. I have no doubt that the statistics our survey found in Autumn of 2020 would now be quite different. I hope that our society continues to be a place for Black medics

to feel comfortable, in a university and city where all too often code-switching and restraint form our mode d’emploi. Now, as president emeritus, I am enjoying watching the society grow from a distance, and I have no doubt that our society will continue to go from strength to strength.