Black at Clare: A History

by Griffin Black

The first African students at Clare College walked through Old Court at the dawn of the twentieth century, and much looked as it does today. Archie and John would have strolled passed the entrance to the Hall, their shoes clacking on the slabs and cobblestones. Perhaps they heard a harmony of voices spill out of the chapel doors and into the courtyard. They would have walked through the archway—flanked by hedges and flowers—and out onto Clare Bridge. Surely, they paused halfway to look out over the Cam, as Clare students have always done. The history of Clare College—nearly 700 years of it—is filled with continuities, gradual shifts, and ruptures. While the beauty of Clare and many of its sensory experiences have remained constant since Archie and John inaugurated the history of Black students at Clare, much has changed.

Clare’s development into a multiracial community of academic excellence has been a gradual process. Unfortunately, one hoping to learn about this process and the early history of Black Clare students will find few, if any, resources. None of the established histories of the College addresses race. These works detail collegiate politics, curricula, wartime life, architectural pursuits, financial woes, and influential alumni.1 Frankly, one will find more historical information on Clare’s cricket fields than its early students of color. The names and stories of those who embodied the changing dynamics of our College have been waiting in the archives.

This essay seeks to start a larger dialogue on the history of Black students at Clare. It is the synthesis of extensive digging in the College’s archives, but it is by no means definitive. Searching for archival unknowns is an inherently shaky process. The author hopes this brief work will stimulate other efforts to create a fuller account of the evolution of the Clare student body.

That said, a clear enough picture arises from archival sources from which we can make key observations and conclusions about Clare’s history. Based on admissions books, histories of the College, obituaries, matriculation photographs, University records, and editions of Lady Clare Magazine and The Clare College Annual, this essay documents nineteen Black Clare students that matriculated between 1916 and 1973:

John Hutton-Mills (1916)

Archibald Casely-Hayford (1918)

Robert Yeboa Oduro (1944)

Ezekiel Minjo (1951)

Theophilus Ayo Bankole (1961)

Nwakamma Agwo Okoro (1961)

Adiele David Nwosu (1962)

Emmanuel Nwanonye Obiechina (1962)

Alexander Obiefoka Enukora Animalu (1962)

Orde Musgrave Coombs (1965)

Koleade Adeniji Abayomi (1966)

Godwin Oludotun Adamolekun (1966)

Osatohamwen Onasere Giwa-Osagie (1966)

Austin Bwandilo Pwele (1967)

Tosan Alfred Rewane (1967)

Eni G. Njoku (1969)

O. A. “Dapo” Ladimeji (1971)

Kwame Anthony Appiah (1972)

Henry Louis Gates, Jr. (1973)

The early history of Black Clare students can helpfully, if arbitrarily, be broken into four phases: the first known students (1916-1918); a roughly forty-year gap with few Black students (1920-1960); the inauguration of a regular stream of Black students matriculating in the 1960s; and the dawn of a more cosmopolitan Clare signified by the simultaneous attendance of Dapo Ladimeji, Kwame Anthony Appiah, and Henry Louis Gates, Jr. Information on students matriculating in the decades after this trio is less difficult to attain, and as such, 1973 is a fitting end to this archival study. Importantly, women were only permitted to matriculate to Clare starting in 1972. As such, further research must be done to detail and acknowledge the contributions of Black women to Clare’s life and history.

The students chronicled in the following pages inaugurated and embodied a lineage of Black Clareites, a group that has fortunately grown considerably larger since. Not all of these individuals have left significant archival footprints. Accessible information about some of the earlier students is obviously scarcer. Much can be gleaned, however, from this eclectic list which includes a classical composer, an anti-colonial politician, a NASA engineer, numerous academics, and two of the leading Black intellectual voices in the present United States. These nineteen students were and are a testament to Black excellence and achievement at Clare College.

1 See Mansfield Duval Forbes, Clare College, 1326-1926: University College 1326-1346, Clare Hall 1346-1856, 2 vols. (Cambridge: Printed for the College at the University Press, 1928); J. R. Wardale, Clare College, University of Cambridge - College Histories (London: F. E. Robinson and Co., 1899); Sir Harry Godwin, Cambridge and Clare (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1985); Richard Eden, Clare College and the Founding of Clare Hall (Cambridge: Clare Hall in the University of Cambridge, 1998); Lindsey Shaw-Miller, ed., Clare Through the Twentieth Century: Portrait of a Cambridge College (Lingfield: Third Millennium, 2001); Michael Lapidge, “College History,” Clare College Cambridge, accessed March 22, 2022, https://www.clare.cam.ac.uk/College-History/.

Clare, Empire, and the Wider World

These individuals were not the first students of color at Clare. A small number of students from South Asia began attending starting in the 1870s. The first of these students seems to be Thomas Edward de Sampayo (Clare, 1878), who would go on to be Chief Justice of the Supreme Court of Ceylon (now Sri Lanka). It is impossible to conclude with certainty that de Sampayo was the first non-white student at Clare, but this seems borne out by the archival record.2 Clare certainly had an international footprint, however small, before this period, but students coming from abroad were almost entirely the children of white British merchants, expats, or colonists. For example, a significant number of white students matriculated from colonial holdings in India in the nineteenth century. That said, de Sampayo’s matriculation in 1878 inaugurated a significant lineage of non-white Clare students from South Asia. These students, though not the focus of this study, deserve an archival investigation of their own.

Looking further in the past, in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, Clare had various links with colonial America and colonial holdings in the Caribbean. Here one finds some explicit and other more ambiguous links between the College and the enslavement of Africans and those of African descent. A more extensive and focused scholarly study needs to be initiated to cement a clearer record of Clare’s involvement in slavery in the Atlantic World.

This would have to include assessing the financial support of Nicholas Ferrar and other monetary and material contributions to Clare from those directly and indirectly involved in the trafficking of human beings.3

Returning to the topic at hand, it is difficult and indeed impossible to disentangle the attendance of the first students of color at Clare from Britain’s colonial history. In general, Clare’s early narrative of student diversity mirrors the arc of British colonialism. It seems that non-white students were slowly admitted to the College from specific regions outside of Europe once Britain had established a colonial presence in them. It appears to have taken a few decades after the establishment of British power before the non-white elites of these places were able to send their sons to England for education. That said, as we will see, some of these early students like John Hutton-Mills and Archie Casely-Hayford went on to become post-colonial leaders and politicians.

2 See de Sampayo’s obituary in Lady Clare Magazine 28, no. 2 (Lent Term 1928), 47.

3 Nicholas Ferrar (1592-1637), who attended Clare, began working with the Virginia Company around 1619. His relationship to the beginnings of slavery in Britain’s American colonies, as well as his ties to Clare, need to be further investigated. See Nicholas W. S. Cranfield, “Ferrar, Nicholas (1593-1637),” in Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, October 4, 2008, https://doi.org/10.1093/ref:odnb/9356. For more on his connection to Clare, see Forbes, Clare College, 1326-1926, vol. 2, esp. 391-588.

The First African Clare Students

John Hutton-Mills and Archibald Casely-Hayford, both from prominent Ghanaian families, were very likely the first Black students at Clare College. Hutton-Mills matriculated in 1916 and Casely-Hayford in 1918. John’s older brother, Thomas, had matriculated at St. Catharine’s College, Cambridge in 1914 to study law, being only the second Black “Catz” student. Alfred Adderley, the first Black student at St. Catharine’s, recalled, “When I went to Cambridge in 1912, there was not a single son of Africa there. I was sorry. But when the first one came I was the first to go and grip his hand, and say, ‘While you are here, you are with me.’” He was most likely speaking of Thomas.4

Thomas Hutton-Mills, Jr. would go on to participate in Kwame Nkrumah’s Convention People’s Party, pushing for Ghana’s independence. He was imprisoned but in 1951 was appointed Minister for Commerce, Industry, and Mines and later the Minister of Health and Labour in Nkrumah’s government. He later became Ghana’s Deputy Commissioner in London and the Ambassador to Liberia.5

John joined his brother Thomas at Cambridge in 1916 but matriculated down the street (and on the river) at Clare.6 His obituary in The Clare Association Annual describes him as the presumed first Ghanaian Clare student. After Cambridge, John pursued medical training at the University of Edinburgh before returning to Accra to practice medicine both as part of the Colonial Government’s medical service and in private practice. It would appear his political views differed from those of his brother, as he was a critic of Nkrumah’s administration. In 1958 he became the first chairman of Ghana’s United Party.7

His classmate Archie arrived in Cambridge in 1918 to study for a Master’s in Law and Economics.8 He was the son of J. E. Casely-Hayford, a famed Gold Coast political leader and author who had studied at Peterhouse, Cambridge.9 After returning to Accra, Archie was a successful lawyer who would play a pivotal role in Ghana’s independence movement. One of his colleagues remembered Archie’s work in the early nationalist movement with admiration:

Although he will be remembered for his scholarship and public spiritedness … he will perhaps be fondly remembered for the very rare, sacrificial and meritorious act of giving up his lucrative appointment in the Judiciary to travel up and down the country offering free legal services to adherents of the now defunct Convention People’s Party when the party leaders were languishing in jail and their supporters hounded by the colonialists, for which admirable and gracious act he earned the proud title: Defender of the Veranda Boys.10

Casely-Hayford represented Kwame Nkrumah and other key anti-colonial leaders, ultimately standing by Nkrumah as he declared Ghana independent at the now-famous press conference at the “Old Polo Ground” on March 6, 1957. He held three major government posts before Ghana achieved independence: Minister of Agriculture and Natural Resources, Minister of Communications, and Minister of State. He represented Ghana at the funeral of King George VI and held the position of Chancellor of the University of Cape Coast. One mourner wrote a sonnet upon Archie’s death that began:

Archie Casely Hayford, lawyer and judge

Has joined his leader in realms of Victory.

Defender of the Boys he did not budge

When gallant fight for liberation raged

Between the Nationals and Colonial power…12

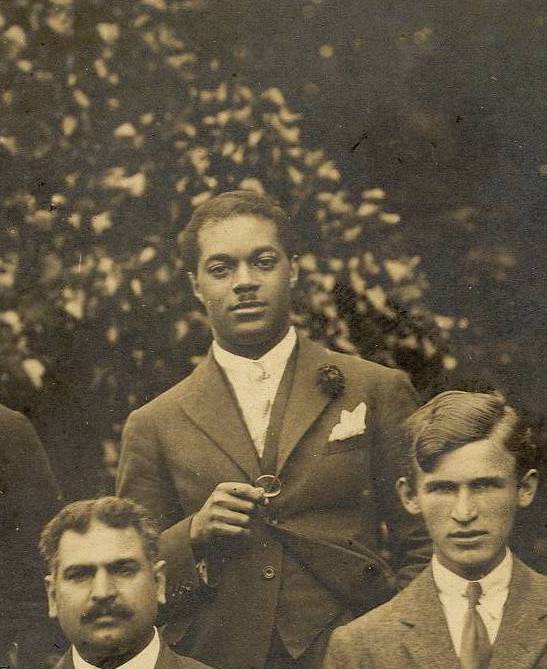

Back to John and Archie’s Clare years, a photograph in the archives spectacularly captures this early moment of Black Cambridge history. The portrait, titled “Cambridge International Fellowship, 1918,” shows a cohort of students from various colleges. Of the nineteen students, seventeen came from countries other than England, and seven hailed from Africa. The students from Africa were racially and ethnically diverse. In this one shot, we see Thomas Hutton-Mills, Jr., John Hutton-Mills, and Archie Casely-Hayford posing together. Under Archie’s name is the title “Vice Pres.” John is faintly labeled as “Musical Director.”13 Given the sparse archival record, we can only imagine what their fellowship and club activities were. This cohort experienced Cambridge at a tumultuous time. Some of them would have seen the University both during wartime and in the conflict’s aftermath.

Archie Casely-Hayford

Archie Casely-Hayford

John Hutton-Mills

John Hutton-Mills

Thomas Hutton-Mills

Thomas Hutton-Mills

After John and Archie, there were only two other Black Clare students in the next forty years. Robert Yeboa Oduro matriculated in 1944 from the Gold Coast, having attained a Colonial Office Scholarship. He studied Natural Sciences and subsequently received a Certificate of Education in London. Returning to teach in the Gold Coast, Oduro was tragically killed in a car accident after accepting a position at the University College of the Gold Coast. He had only graduated from Clare about five years earlier. An obituary published by Clare recalled, “It would have been difficult to find a more worthy representative of the Gold Coast to send to Cambridge; he had a natural charm of disposition and a grace of manner which won him a very wide circle of friends. … His early death is a sad loss to education in the Gold Coast.”14 Around the time of Oduro’s passing, Ezekial Minjo arrived at Clare and studied mathematics.15 Born in Kenya, Minjo studied in South Africa before traveling to Cambridge.16 Little more is presently known about his time after Clare.

4 “Thomas Hutton-Mills Jnr (14 November 1894–11 May 1959),” St. Catharine’s College, Cambridge, accessed April 2, 2022, https://www.caths.cam.ac.uk/about-us/history/black-history/t-hutton-mills-jnr. Also see, “Our Black History,” St Catharine’s College, Cambridge, accessed April 2, 2022, https://www.caths.cam.ac.uk/about-us/history/black-history.

5 Alfred Adderly, “THOMAS HUTT[U]N-MILLS,” St Catharine's College Society Magazine, September 1859, 39.

6 For John’s entry in the Clare Admissions book, see page including “10 Octr 1916,” in “Register of Admissions of Clare College beginning October 18, 1871,” CCAC/2/1/1/2, Clare College Archives, Cambridge, England.

7 The Clare Association Annual, 1967, 84.

8 For Archie’s entry in the Clare Admissions book, see page beginning “Date of Admission 12 Oct. 1917,” in “Register of Admissions of Clare College beginning October 18, 1871.”

9 For more on Joseph Ephraim Casely-Hayford, see David U. Enweremadu, “Casely-Hayford, Joseph Ephraim (1866-1930),” in Dictionary of African Biography, ed. Henry Louis Gates, Jr., Emmanuel Akyeampong, and Steven J. Niven (Oxford University Press, 2011), https://www.oxfordreference.com/view/10.1093/acref/9780195382075.001.0001/acref-9780195382075-e-0422. Also see “Joseph Ephraim Casely Hayford (Peterhouse, 1896),” The Black Cantabs Research Society, July 28, 2018, https://www.blackcantabs.org/post/joseph-ephraim-casely-hayford-peterhouse-1896.

10Kodwo Mensah, “Archie As I Knew Him,” Daily Graphic (Ghana), August 31, 1977. “Verandah Boys” was a term for Nkrumah’s supporters, who were generally seen as representing the interests of a lower social class. See George M. Bob-Milliar, “Verandah Boys Versus Reactionary Lawyers: Nationalist Activism in Ghana, 1946–1956,” The International Journal of African Historical Studies 47, no. 2 (2014): 287–318, esp. 288.

11Mensah, “Archie As I Knew Him.”

12J. Benibengor Blay, “A Sonnet,” Daily Graphic, August 31, 1977.

13“Cambridge International Fellowship, 1918,” Photograph, 1918, CCPH/2/5/CIF/1918, Clare College Archives, Cambridge, England.

14The Clare Association Annual, 1952, 61. Also see entry in “Index to Obituaries of Clare College Alumni Published in The Lady Clare Magazine or The Clare Association Annual 1920 Onwards,” Clare College Archives, Cambridge, England.

15Clare Review, Issue 4, 2020-2021, 84.

The Next Wave

The 1960s saw a substantial influx of Black students matriculating at Clare, many of them from Nigeria. In 1961, Nwakamma Agwo Okoro and T. Ayo Bankole matriculated together. This marked the first matriculation year with multiple Black students. Okoro was born in Nigeria and came to Clare after studying at the University of Birmingham.17 At Clare, he was the William Senior Scholar in Comparative Law, the scholarship funding his doctoral research. He published his work in 1966, The Customary Laws of Succession in Eastern Nigeria and the Statutory and Judicial Rules Governing their Application. Okoro’s research was pathbreaking in Cambridge. As one book reviewer noted, “It is a sad illustration of the lack of provision in our older universities for non-Western European legal systems that although the degree of Doctor of Philosophy was obtained from Cambridge the actual supervision was done by Professor A. N. Allott in London.”18 Returning to Nigeria, Okoro would have an accomplished legal career as a barrister and a Solicitor of the Supreme Court of Nigeria.19

Moving from law to music — Ayo Bankole was born in Nigeria in 1935 and began as a chorister at Cathedral Church of Christ in Lagos. Receiving a Federal Government Scholarship to Guildhall School of Music and Drama, he studied in London before winning an organ scholarship to Clare in 1961. While at Clare, he composed his Three Toccatas for organ. As he finished his B.A. in Music, he became a Fellow of the Royal College of Organists and soon after won a Rockefeller Foundation Fellowship to research ethnomusicology at the University of California, Los Angeles. He moved back to Nigeria in 1966 and worked as Senior Producer in Music at the Nigerian Broadcasting Corporation and then as a lecturer at the University of Lagos. Bankole labored extensively to expand music education in the city, working with several student and adult choirs and music organizations.20

His compositions often combined aspects of the European classical style with Nigerian lyrics, instruments, melodies, and themes, and he is credited with spurring the emergence of the Nigerian art music movement.21 Other key works included Sonata No. 2 and Adura Fun Alafia (Prayer for Peace), which was composed during a period of civil war in Nigeria. One scholar notes that Bankole’s FESTAC Cantata no. 4 “is truly a multicultural composition” that exhibits his combination of European and African musical traditions.

Flutes and trumpets comingle with Nigerian instruments like the sekere and iya-dundun.22 Another scholar similarly writes, “Bankole's compositional style embraces eclectic influences, including Yoruba music melded with European tonality, modality, whole tone scales, and chromaticism, to form a nationalistic style.”23 Bankole’s body of work is a testament to the contributions of Black artists to Clare’s proud history of composition and sacred music.

A trio of African students matriculated in 1962, two of them becoming leading Nigerian academics. Alexander Obiefoka Enukora Animalu is a Nigerian physicist and astronomer who researched and taught at many universities in the United States before spending most of his career at the University of Nigeria. Animalu received an M.A. and Ph.D. in Physics at Clare and published extensive work that he conducted at Cambridge’s Cavendish Laboratory. His published doctoral research has been highly influential, especially his tables of Fourier transforms.24 . Animalu later remembered, “The reaction to my tables of the Fourier transforms of the model potential was very favourable, even among the pioneers in the field. At Cambridge there was not as much enthusiasm … and for a while the results were distributed as preliminary. This produced a crisis situation in which I struck out on my own to issue these preliminary results.” Once the gravity of his findings was recognized, Animalu moved to the United States, where he held positions at Stanford University, the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, the University of Missouri at Rolla, Drexel University, and the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. While working as a physicist in MIT’s Lincoln Laboratory, he published his Intermediate Quantum Theory of Crystalline Solids.26 In 1976, Animalu became Professor of Theoretical Solid State Physics at the University of Nigeria, Nsukka, eventually holding several prestigious positions, including the Head of Department of Physics and the Dean of the Faculty of Physical Sciences.

Animalu has continued his scholarship, with a special focus on the nexus of astronomy and African culture. He once stated in a lecture, “I have always dreamt that a time would come when we Africans could sit back and reconstruct the African world view in mathematical terms and stand it side by side with other world views for the benefit of all mankind. ... Such a revolution in thought and education should be able to make us capable of ‘comprehending the problems of the earth, or of the solar system, or of the galaxy, or of the universe.’”27 Of particular interest is his “African Perspective on the Theory of Everything,” which interacts with the theories of another Cantab physicist, Stephen Hawking.28

Emmanuel Obiechina matriculated with Animalu and received his Ph.D. in English. He specialized in English and African literature, holding positions at universities in Nigeria and the United States. His most influential books were Language and Theme: Essays on African Literature; Culture, Tradition and Society in the West African Novel; and An African Popular Literature: A Study of Onitsha Market Pamphlets.29 His other academic publications spanned a range of topics.30 In 2002-2003, Obiechina was a Visiting Scholar at the Department of African and African American Studies at Harvard as well as a fellow at Harvard’s W.E.B. Du Bois Research Institute. . While there, he intersected with fellow Clare alumnus and scholar, Henry Louis Gates, Jr.31 Little has been found so far about Animalu and Obiechina’s classmate, Adiele David Nwosu.

Orde Musgrave Coombs matriculated at Clare in 1965 after graduating from Yale University. Born in St. Vincent, he appears to have been the first Black Caribbean Clare Student.32 At Yale, Coombs also intersected with Gates, perhaps even discussing the opportunity to attend Cambridge.33 While in New Haven, Coombs became the first Black member of the Yale’s oldest secret society, Skull and Bones. His induction attracted significant media attention and appeared in Jet magazine in 1964.34 Coombs left Cambridge soon after arriving, feeling drawn back to the United States to be present during the intensifying push for civil rights for Black Americans. He would publish several works and was an editor for New York Magazine before dying in 1984 of cancer.35

Godwin Oludotun Adamolekun matriculated in 1966 and received a master’s degree in Mechanical Science. He went on to work in the oil and gas industry and is currently the chairman of Euroflow Designs, “an indigenous engineering and design, project management, and technical support services company operating in the oil and gas sector in Nigeria.”36 Koleade Adeniji Abayomi was a classmate of Adamolekun’s who became a prominent jurist and constitutional thinker in Nigeria. He would become the Director General of the Nigerian Law School and was part of the Constitution Drafting Commission formed in 1975 to draft a new constitution for the nation.37 He passed away in 2020. Osatohamwen Onasere Giwa-Osagie, the last of the trio of Nigerians that matriculated in 1966, did his undergraduate work in medicine at Clare before becoming a prominent obstetrician in his home country. He has been a key faculty member of the College of Medicine at the University of Lagos for many years.38 The following year, Tosan Alfred Rewane matriculated to study Natural Sciences. While a Cambridge student, he was President of the African Society. A successful business leader in Nigeria, he published his Niger Delta: A Path to Prosperity in 2007.39 Rewane matriculated alongside Austin Bwandilo Pwele from Malawi. Pwele studied at the Institute of Public Administration in Blantyre, Malawi, but little more information on him has been found in the archives.40

In 1969, Eni G. Njoku arrived at Clare as an undergraduate. Graduating with his B.A. in Electrical and Natural Sciences, he went on to receive his master’s and doctorate at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. He then began working in NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory at the California Institute of Technology. Dr. Njoku spent nearly 40 years at NASA’s JPL, specializing in “Earth from space using satellite microwave sensing,” receiving multiple awards, and holding academic positions at Harvey Mudd College and MIT, among others.41 He has also published numerous academic articles.42

16“Admissions April 16th, 1951,” in “Admissions 1951-1979,” CCAC/2/1/1/3, Clare College Archives, Cambridge, England.

17 “Admissions 9th October [1961],” in “Admissions 1951-1979.” no. 3 (October 1967): 750–51, quote on 750.

18J. Duncan M. Derrett, Review: “Nwakamma Okoro: The Customary Laws of Succession in Eastern Nigeria and the Statutory and Judicial Rules Governing Their Application,” Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies, University of London 30, Fiftieth Anniversary Volume, no. 3 (October 1967): 750–51, quote on 750.

19The few biographical details on Okoro that have been found for this study are from his book. Nwakamma Okoro, The Customary Laws of Succession in Eastern Nigeria and the Statutory and Judicial Rules Governing Their Application, Law in Africa 15 (London/Lagos: Sweet & Maxwell/African Universities Press, 1966).

20See Bankole’s obituary in The Clare Association Annual, 1986-7, 52; Godwin Sadoh, “Ayo Bankole at 80,” The Musical Times 156, no. 1930 (Spring 2015): 73–88; Philip Herbert, “Bankole, Ayo (1935-1976),” in The Oxford Companion to Black British History, ed. David Dabydeen, John Gilmore, and Cecily Jones (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2007), https://www.oxfordreference.com/view/10.1093/acref/9780192804396.001.0001/acref-9780192804396-e-36; and Olabode F. Omojola, “Contemporary Art Music in Nigeria: An Introductory Note on the Works of Ayo Bankole (1935–76),” Africa 64, no. 4 (October 1994): 533–43.

21Omojola, “Contemporary Art Music in Nigeria.”

22Sadoh, “Ayo Bankole at 80,” quote and description of instruments on 81. Sadoh provides a helpful list of Bankole’s works, 86-8.

23Herbert, “Bankole, Ayo (1935-1976).”

24A. O. E. Animalu and V. Heine, “The Screened Model Potential for 25 Elements,” The Philosophical Magazine 12, no. 120 (December 1, 1965): 1249–70.

25A. O. E. Animalu, “This Week’s Citation Classic,” Current Contents, no. 5 (January 31, 1983): 16.

26 A. O. E. Animalu, Intermediate Quantum Theory of Crystalline Solids (Englewood Cliffs, N.J.: Prentice-Hall, 1977).

27Animalu quoted in Johnson O. Urama and Jarita C. Holbrook, “The African Cultural Astronomy Project,” Proceedings of the International Astronomical Union 5, no. 260 (January 2009), 49.

28A. O. E. Animalu and Catherine O. Acholonu, “Hyperspace and the Torus Revisited: An African Perspective on the Theory of Everything,” African Journal of Physics 3 (2010): 31–50. For a helpful summary of Professor Animalu’s life and career, see “University of Nigeria Staff Profile - Prof. Animalu Alexander O.E.,” University of Nigeria, accessed April 6, 2022. http://www.unn.edu.ng/internals/staff/viewProfile/NDQw.

29Emmanuel N. Obiechina, Language and Theme: Essays on African Literature (Washington, D.C.: Howard University Press, 1990); Culture, Tradition and Society in the West African Novel (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1975); An African Popular Literature: A Study of Onitsha Market Pamphlets (London: Cambridge University Press, 1973).

30Emmanuel N. Obiechina, “Cultural Nationalism in Modern African Creative Literature,” African Literature Today 1, no. 2 (1968): 24–35; “The Writer and His Commitment in Contemporary Nigerian Society,” Okike: An African Journal of New Writing, no. 27/28 (1988): 1–9; “Parables of Power and Powerlessness: Exploration in Anglophone African Fiction Today,” African Issues 20, no. 2 (1992): 17–25; “Narrative Proverbs in the African Novel,” Research in African Literatures 24, no. 4 (1993): 123–40.

31WGBH Educational Foundation, “Emmanuel M. [sic.] Obiechina,” WGBH - Forum Network, accessed April 11, 2022, https://forum-network.org/speakers/obiechina-emmanuel-m/.

32Professor Tony Badger, former Master of Clare College, has perceptively hypothesized, in communication with the author, that there might have been British Afro-Caribbean Clare students before this period. No such students were found during the research for this study, but future researchers should investigate this further.

33Gates described this in correspondence with the author.

34“Oldest Yale Club Initiates First Negro,” Jet, May 28, 1964.

35For more on his decision to return to the United States, see the autobiographical quotes accessible at Ronnie D. Lankford, Jr., “Coombs, Orde M. 1939–1984,” Encyclopedia.com, accessed May 20, 2022, https://www.encyclopedia.com/education/news-wires-white-papers-and-books/coombs-orde-m-1939-1984. “Orde Coombs, Writer, Dies; Former Editor at New York,” New York Times, September 1, 1984. For Coombs’ major publications, see Orde Coombs, Do You See My Love for You Growing? (New York: Dodd, Mead & Company, 1972); Orde Coombs, ed., What We Must See: Young Black Storytellers (New York: Dodd, Mead & Company, 1971); Orde Coombs, ed., We Speak as Liberators: Young Black Poets; an Anthology (New York: Dodd, Mead & Company, 1970).

36 Euroflow Designs Ltd., “Brief History of the Company, Euroflow (COMPANY PROFILE – EDL/BD/CP/2021-001),” July 2021, accessed May 20, 2022, https://www.euroflowdesigns.com/site/assets/files/1015/edl_company_profile_-_july_2021-1.pdf; company quote from “Euroflow Designs - Home,” Euroflow Designs Ltd., accessed April 8, 2022, https://www.euroflowdesigns.com/.

37Bashorun Randle, “An Empty Seat for Koleade Adeniji Abayomi, SAN; OON,” Businessday NG, June 8, 2020, https://businessday.ng/columnist/article/an-empty-seat-for-koleade-adeniji-abayomi-san-oon/; Ogunsakin Mustapha, “Former DG, Nigerian Law School, Dr Kole Abayomi Dies At 79,” The Gavel International, April 2, 2020, https://thegavel.com.ng/13865/; Ademola Olonilua, Eric Dumo, and “Punchng,” “At 21, My Dad Gave Me His Will, Access to His Accounts – Abayomi, Ex-DG, Nigerian Law School,” Punch, July 1, 2017, https://punchng.com/at-21-my-dad-gave-me-his-will-access-to-his-accounts-abayomi-ex-dg-nigerian-law-school/.

38Emeka Obasi, “Ibadan Retired Giwa-Osagie,” Vanguard News, August 22, 2020, https://www.vanguardngr.com/2020/08/ibadan-retired-giwa-osagie/; Seye Kehinde, “Why I Decided To Go & Study Medicine In 1966 - Prof. OSATO OSAGIE,” City People Magazine, April 17, 2017, https://www.citypeopleonline.com/decided-go-study-medicine-1966-prof-osato-osagie/; “My House Is like a Zoo – Prof Osato Giwa-Osagie, Gynaecologist,” The Sun (Nigeria), accessed April 8, 2022, https://www.sunnewsonline.com/my-house-is-like-a-zoo-prof-osato-giwa-osagie-gynaecologist/.

39 Tosan Alfred Rewane, Niger Delta: A Path to Prosperity (Central Milton Keynes: AuthorHouse, 2007).

40Oddly, Pwele does not appear in the Clare class portrait from the 1967 matriculation. He is listed as matriculating at Clare in The Annual Register of the University of Cambridge for the Year 1966-67 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1967), 1358. See “Admissions 9 October 1967,” in “Admissions 1951-1979.”

41MLK Visiting Professors and Scholars Program - Massachusetts Institute of Technology, “Eni Njoku,” MLK Visiting Professors and Scholars Program, accessed April 9, 2022, https://mlkscholars.mit.edu/scholars/eni-njoku. Quote from Eni G. Njoku, “Eni G. Njoku,” LinkedIn, accessed April 9, 2022, https://www.linkedin.com/in/enignjoku/.

42L. Tsang, E. Njoku, and J. A. Kong, “Microwave Thermal Emission from a Stratified Medium with Nonuniform Temperature Distribution,” Journal of Applied Physics 46, no. 12 (December 1975): 5127–33; Eni G. Njoku and Jin-Au Kong, “Theory for Passive Microwave Remote Sensing of Near-Surface Soil Moisture,” Journal of Geophysical Research 82, no. 20 (1977): 3108–18; R. Hofer, E. G. Njoku, and J. W. Waters, “Microwave Radiometric Measurements of Sea Surface Temperature from the Seasat Satellite: First Results,” Science 212, no. 4501 (June 19, 1981): 1385–87; Eni G. Njoku, “Reflection of Electromagnetic Waves at a Biaxial–Isotropic Interface,” Journal of Applied Physics 54, no. 2 (February 1983): 524–30; Eni G. Njoku and Dara Entekhabi, “Passive Microwave Remote Sensing of Soil Moisture,” Journal of Hydrology, Soil Moisture Theories and Observations, 184, no. 1 (October 1, 1996): 101–29; E.G. Njoku et al., “Global Survey and Statistics of Radio-Frequency Interference in AMSR-E Land Observations,” IEEE Transactions on Geoscience and Remote Sensing 43, no. 5 (May 2005): 938–47. See MLK Visiting Professors and Scholars Program - Massachusetts Institute of Technology, “Eni Njoku,” for a partial bibliography.

Ladimeji, Appiah, Gates, and a Multiracial Clare

The matriculation of Dapo Ladimeji, Kwame Anthony Appiah, and Henry Louis Gates, Jr. at Clare, in 1971, 1972, and 1973 respectively, represented in many ways the beginning of the present cosmopolitan era of Clare’s history. This was a time of significant change at Clare on many fronts, as women first began matriculating in 1972. Appiah chose to apply to Clare after visiting with a family friend. He later remembered, “I had a terrific time at Clare College.”

Of course, there were very few non-white students in Clare at the time. He recalled:

I met Skip Gates, who arrived as a Mellon Fellow from Yale. He tells the story that after the fifth person asked him if we had met, he decided I must be black, too! … There was only one other black person among the undergraduates, a philosophy student named Dapo Ladimeji, from a Nigerian family. Basically, though, I socialized in the evenings, read and wrote all night, woke up late, and had one or two tutorials a week with great supervisors... Philip Pettit, for example. The ideal life for me: philosophy and fun. That and falling in and out of love fairly often.43

Appiah, Gates, and Ladimeji were close during their Clare years, sharing many spirited political and philosophical debates in Thirkill Court.44 As this trio enjoyed their first year at Clare, Wole Soyinka—then an instructor at Churchill College—wrote his classic play “Death and the King’s Horsemen.” He invited Gates and Ladimeji to a special staged reading of a draft of the work. Soyinka would win the Nobel Prize in Literature in 1986. Ladimeji continued teaching at Westminster University and later worked for many years as an accountant in London. He is now part of the Institute of African and Diaspora Studies at the University of Lagos.45 Gates and Appiah stayed at Clare and received doctorates in English and Philosophy, respectively. This Clare pair then moved to New Haven, Connecticut, where both held positions at Yale University. Appiah is now Professor of Philosophy and Law at New York University, while Professor Gates is the Alphonse Fletcher University Professor at Harvard University.

Even by this period, Clare was certainly less open to the study of Black culture than it is today. Professor Gates recalled the unfortunate moment when he proposed writing a dissertation on “black literature” to his tutor in English at Clare: : “[T]he tutor replied with great disdain, ‘Tell me, sir, … what is black literature?’ When I responded with a veritable bibliography of texts written by authors who were black, his evident irritation informed me that I had taken as a serious request for information what he had intended as a rhetorical question.”46 Fortunately, Gates crafted his dissertation47 as he saw fit and—like the other students in this study—was undeterred by scoffing tutors and prejudiced expectations.

Converting Clare into an outward-facing, international, and welcoming intellectual community required more than the attendance or inclusion of these nineteen individuals. It took their efforts as students, peers, intellectuals, friends, teammates, colleagues, and alumni. For these efforts, all Clare students owe a debt of gratitude. Of course, there is significant work still to be done to make Clare a truly equitable institution. In his recent work Cosmopolitanism: Ethics in a World of Strangers, Professor Appiah explains that a proper cosmopolitan worldview is composed of two parts: a respect for the universal responsibilities all human beings have in relation to each other, and an appreciation of people’s cultural and geographical differences.48 Such a framework allows us to simultaneously espouse that all people are equal and inherently kindred and that their differences are valuable. All Clare students, past and present, have contributed to making Clare a place that exemplifies both the unity and diversity of humankind. The nineteen individuals covered in this study have played a unique and venerable part in this process. They should be further commemorated and remembered with gratitude for their work creating a cosmopolitan Clare.

43Clifford Sosis and Kwame Anthony Appiah, Untitled Interview with Kwame Anthony Appiah on July 28, 2016, What Is It Like to Be a Philosopher?, July 28, 2016, http://www.whatisitliketobeaphilosopher.com/#/kwame-anthony-appiah/.

44Gates described this in correspondence with the author.

45“Dapo Ladimeji – Chair,” African Century Journal, accessed May 19, 2022, https://african-century.org/dapo-ladimeji-chair/. For two examples of Ladimeji’s published writings around the time of his studying at Clare, see O.A. Ladimeji, “Philosophy and the Third World,” Radical Philosophy, October 1972, 16–18; “Flew and the Revival of Social Darwinism,” Philosophy 49, no. 187 (January 1974): 97–101.

46Henry Louis Gates, Jr., “Introduction, ‘Tell Me, Sir, ... What Is “Black” Literature?,’” in The Henry Louis Gates, Jr. Reader, by Henry Louis Gates, Jr., ed. Abby Wolf (New York: Basic Civitas, 2012).

47Henry Louis Gates, Jr., “The History and Theory of Afro-American Literary Criticism, 1773-1831: The Arts, Aesthetic Theory, and the Nature of the African” Doctoral Thesis, University of Cambridge (1978).

48Kwame Anthony Appiah, Cosmopolitanism: Ethics in a World of Strangers (London: Penguin Books, 2006), xiii.

Acknowledgments

I would like to thank the tremendous librarians and archivists at Clare: Catherine Reid, Julie Hope, Claire Butlin, and Jonathan Smith. This essay would be nowhere near as detailed or complete without the help of Claire Butlin, who spent many days in the Clare College Archives with me. Professor Tony Badger, former Master of Clare, kindly reviewed a draft of this work and offered crucial insights. Kwame Anthony Appiah supplied essential information on Ghanaian history and his time at Clare. I have thoroughly enjoyed working with the Development team at Clare and am thankful for their support of this research.

Collaborating with Professor Henry Louis Gates, Jr. has been a true pleasure and a highlight of my time here at Clare. I am grateful to both him and the College for the opportunity to conduct this project.

Works Cited:

All manuscript materials consulted are available at the Clare College Archives, including the “Index to Obituaries of Clare College Alumni Published in The Lady Clare Magazine or The Clare Association Annual 1920 Onwards.” The Archives and Clare’s Forbes Mellon Library house many editions of the various histories of the College.

The online “A Cambridge Alumni Database” based on the research of John Venn, John Archibald Venn, and A.B. Emden (among others) is an invaluable resource provided by the University of Cambridge and is accessible at: https://venn.lib.cam.ac.uk/.

Periodicals

Clare Review

Daily Graphic (Ghana)

Jet

Lady Clare Magazine

New York Times

The Annual Register of the University of Cambridge

The Clare Association Annual

Secondary Sources

Adderly, Alfred. “THOMAS HUTT[U]N-MILLS.” St Catharine’s College Society Magazine, September 1859.

African Century Journal. “Dapo Ladimeji – Chair,” September 22, 2018. https://african-century.org/dapo-ladimeji-chair/.

Animalu, A. O. E. “Electronic Structure of Transition Metals. I. Quantum Defects and Model Potential.” Physical Review B 8, no. 8 (October 15, 1973): 3542–54.

———. Intermediate Quantum Theory of Crystalline Solids. Englewood Cliffs, N.J.: Prentice-Hall, 1977.

———. “Non-Local Dielectric Screening in Metals.” The Philosophical Magazine: A Journal of Theoretical Experimental and Applied Physics 11, no. 110 (February 1, 1965): 379–88.

———. “The Pressure Dependence of the Electrical Resistivity Thermopower and Phonon Dispersion in Liquid Mercury.” Advances in Physics 16, no. 64 (October 1, 1967): 605–15.

———. “This Week’s Citation Classic.” Current Contents, no. 5 (January 31, 1983): 16.

Animalu, A. O. E., and Catherine O. Acholonu. “Hyperspace and the Torus Revisited: An African Perspective on the Theory of Everything.” African Journal of Physics 3 (2010): 31–50.

Animalu, A. O. E., F. Bonsignori, and V. Bortolani. “The Phonon Spectra of Alkali Metals and Aluminium.” Il Nuovo Cimento B (1965-1970) 44, no. 1 (July 1, 1966): 159–71.

Animalu, A. O. E., and William Cochran. “The Total Electronic Band Structure Energy for 29 Elements.” Proceedings of the Royal Society of London. Series A. Mathematical and Physical Sciences 294, no. 1438 (October 4, 1966): 376–92.

Animalu, A. O. E., and V. Heine. “The Screened Model Potential for 25 Elements.” The Philosophical Magazine: A Journal of Theoretical Experimental and Applied Physics 12, no. 120 (December 1, 1965): 1249–70.

Appiah, Kwame Anthony. Cosmopolitanism: Ethics in a World of Strangers. London: Penguin Books, 2006.

The Black Cantabs Research Society. “Home,” July 28, 2018. https://www.blackcantabs.org.

———. “Joseph Ephraim Casely Hayford (Peterhouse, 1896),” July 28, 2018. https://www.blackcantabs.org/post/joseph-ephraim-casely-hayford-peterhouse-1896.

Blay, J. Benibengor. “A Sonnet.” Daily Graphic, August 31, 1977.

Bob-Milliar, George M. “Verandah Boys Versus Reactionary Lawyers: Nationalist Activism in Ghana, 1946–1956.” The International Journal of African Historical Studies 47, no. 2 (2014): 287–318.

Coombs, Orde. Do You See My Love for You Growing? New York: Dodd, Mead & Company, 1972.

———, ed. We Speak as Liberators: Young Black Poets; an Anthology. New York: Dodd, Mead & Company, 1970.

———, ed. What We Must See: Young Black Storytellers. New York: Dodd, Mead & Company, 1971.

Cranfield, Nicholas W. S. “Ferrar, Nicholas (1593-1637).” In Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, October 4, 2008. https://doi.org/10.1093/ref:odnb/9356.

Derrett, J. Duncan M. Review: “Nwakamma Okoro: The Customary Laws of Succession in Eastern Nigeria and the Statutory and Judicial Rules Governing Their Application.” Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies, University of London 30, Fiftieth Anniversary Volume, no. 3 (October 1967): 750–51.

Eden, Richard. Clare College and the Founding of Clare Hall. Cambridge: Clare Hall in the University of Cambridge, 1998.

Enweremadu, David U. “Casely-Hayford, Joseph Ephraim (1866-1930).” In Dictionary of African Biography, edited by Henry Louis Gates, Jr., Emmanuel Akyeampong, and Steven J. Niven. Oxford University Press, 2011. https://www.oxfordreference.com/view/10.1093/acref/9780195382075.001.0001/acref-9780195382075-e-0422.

Euroflow Designs Ltd. “Euroflow Designs - Home.” Accessed April 8, 2022. https://www.euroflowdesigns.com/.

———. “Brief History of the Company, Euroflow (COMPANY PROFILE – EDL/BD/CP/2021-001),” July 2021. https://www.euroflowdesigns.com/site/assets/files/1015/edl_company_profile_-_july_2021-1.pdf.

Forbes, Mansfield Duval. Clare College, 1326-1926: University College 1326-1346, Clare Hall 1346-1856. 2 vols. Cambridge: Printed for the College at the University Press, 1928.

Gates, Jr., Henry Louis. “Introduction, ‘Tell Me, Sir, ... What Is “Black” Literature?’” In The Henry Louis Gates, Jr. Reader, by Henry Louis Gates, Jr., edited by Abby Wolf. New York: Basic Civitas, 2012.

———. “The History and Theory of Afro-American Literary Criticism, 1773-1831: The Arts, Aesthetic Theory, and the Nature of the African.” Doctoral Thesis, University of Cambridge, 1978.

Godwin, Sir Harry. Cambridge and Clare. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1985.

Herbert, Philip. “Bankole, Ayo (1935-1976).” In The Oxford Companion to Black British History, edited by David Dabydeen, John Gilmore, and Cecily Jones. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2007. https://www.oxfordreference.com/view/10.1093/acref/9780192804396.001.0001/acref-9780192804396-e-36.

Hofer, R., E. G. Njoku, and J. W. Waters. “Microwave Radiometric Measurements of Sea Surface Temperature from the Seasat Satellite: First Results.” Science 212, no. 4501 (June 19, 1981): 1385–87.

Kehinde, Seye. “Why I Decided To Go & Study Medicine In 1966 - Prof. OSATO OSAGIE.” City People Magazine (blog), April 17, 2017. https://www.citypeopleonline.com/decided-go-study-medicine-1966-prof-osato-osagie/.

Ladimeji, O. A. “Flew and the Revival of Social Darwinism.” Philosophy 49, no. 187 (January 1974): 97–101.

———. “Philosophy and the Third World.” Radical Philosophy, October 1972, 16–18.

Lankford, Jr., Ronnie D. “Coombs, Orde M. 1939–1984.” Encyclopedia.com. Accessed May 20, 2022. https://www.encyclopedia.com/education/news-wires-white-papers-and-books/coombs-orde-m-1939-1984.

Lapidge, Michael. “College History.” Clare College Cambridge. Accessed March 22, 2022. https://www.clare.cam.ac.uk/College-History/.

MLK Visiting Professors and Scholars Program - Massachusetts Institute of Technology. “Eni Njoku.” Accessed April 9, 2022. https://mlkscholars.mit.edu/scholars/eni-njoku.

Much Loved. “Memorial to Prof. Emmanuel Nwanonye Obiechina. PhD. Ugoezue of Nkpor.” Accessed April 11, 2022. https://profemmanuelobiechina.muchloved.com/Lifestories/6509631.

Mensah, Kodwo. “Archie As I Knew Him.” Daily Graphic, August 31, 1977.

Mustapha, Ogunsakin. “Former DG, Nigerian Law School, Dr Kole Abayomi Dies At 79.” The Gavel International, April 2, 2020. https://thegavel.com.ng/13865/.

“My House Is like a Zoo – Prof Osato Giwa-Osagie, Gynaecologist.” The Sun (Nigeria). Accessed April 8, 2022. https://www.sunnewsonline.com/my-house-is-like-a-zoo-prof-osato-giwa-osagie-gynaecologist/.

Njoku, E.G., P. Ashcroft, T.K. Chan, and Li Li. “Global Survey and Statistics of Radio-Frequency Interference in AMSR-E Land Observations.” IEEE Transactions on Geoscience and Remote Sensing 43, no. 5 (May 2005): 938–47.

Njoku, Eni G. “Eni G. Njoku.” LinkedIn. Accessed April 9, 2022. https://www.linkedin.com/in/enignjoku/.

———. “Reflection of Electromagnetic Waves at a Biaxial–Isotropic Interface.” Journal of Applied Physics 54, no. 2 (February 1983): 524–30.

Njoku, Eni G., and Dara Entekhabi. “Passive Microwave Remote Sensing of Soil Moisture.” Journal of Hydrology, Soil Moisture Theories and Observations, 184, no. 1 (October 1, 1996): 101–29.

Njoku, Eni G., and Jin-Au Kong. “Theory for Passive Microwave Remote Sensing of Near-Surface Soil Moisture.” Journal of Geophysical Research 82, no. 20 (1977): 3108–18.

Nwankwo, Chimalunm. “Tribute: Emmanuel Obiechina: A Great Escort.” Vanguard News, November 14, 2010. https://www.vanguardngr.com/2010/11/tribute-emmanuel-obiechina-a-great-escort/.

Obasi, Emeka. “Ibadan Retired Giwa-Osagie.” Vanguard News, August 22, 2020. https://www.vanguardngr.com/2020/08/ibadan-retired-giwa-osagie/.

Obiechina, Emmanuel N. An African Popular Literature: A Study of Onitsha Market Pamphlets. London: Cambridge University Press, 1973.

———. “Cultural Nationalism in Modern African Creative Literature.” African Literature Today 1, no. 2 (1968): 24–35.

———. Culture, Tradition and Society in the West African Novel. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1975.

———. Language and Theme: Essays on African Literature. Washington, D.C.: Howard University Press, 1990.

———. “Narrative Proverbs in the African Novel.” Research in African Literatures 24, no. 4 (1993): 123–40.

———. “Parables of Power and Powerlessness: Exploration in Anglophone African Fiction Today.” African Issues 20, no. 2 (1992): 17–25.

———. “The Writer and His Commitment in Contemporary Nigerian Society.” Okike: An African Journal of New Writing, no. 27/28 (1988): 1–9.

Okoro, Nwakamma. The Customary Laws of Succession in Eastern Nigeria and the Statutory and Judicial Rules Governing Their Application. Law in Africa 15. London/Lagos: Sweet & Maxwell/African Universities Press, 1966.

Olonilua, Ademola, Eric Dumo, and “Punchng.” “At 21, My Dad Gave Me His Will, Access to His Accounts – Abayomi, Ex-DG, Nigerian Law School.” Punch, July 1, 2017. https://punchng.com/at-21-my-dad-gave-me-his-will-access-to-his-accounts-abayomi-ex-dg-nigerian-law-school/.

Omojola, Olabode F. “Contemporary Art Music in Nigeria: An Introductory Note on the Works of Ayo Bankole (1935–76).” Africa 64, no. 4 (October 1994): 533–43.

Randle, Bashorun. “An Empty Seat for Koleade Adeniji Abayomi, SAN; OON.” Businessday NG, June 8, 2020. https://businessday.ng/columnist/article/an-empty-seat-for-koleade-adeniji-abayomi-san-oon/.

Rewane, Tosan Alfred. Niger Delta: A Path to Prosperity. Central Milton Keynes: AuthorHouse, 2007.

Sadoh, Godwin. “Ayo Bankole at 80.” The Musical Times 156, no. 1930 (Spring 2015): 73–88.

Shaw-Miller, Lindsey, ed. Clare Through the Twentieth Century: Portrait of a Cambridge College. Lingfield: Third Millennium, 2001.

Sosis, Clifford, and Kwame Anthony Appiah. Untitled Interview with Kwame Anthony Appiah on July 28, 2016. What Is It Like to Be a Philosopher?, July 28, 2016. http://www.whatisitliketobeaphilosopher.com/#/kwame-anthony-appiah/.

St Catharine’s College, Cambridge. “Our Black History.” Accessed April 2, 2022. https://www.caths.cam.ac.uk/about-us/history/black-history.

———. “Thomas Hutton-Mills Jnr (14 November 1894–11 May 1959).” Cambridge. Accessed April 2, 2022. https://www.caths.cam.ac.uk/about-us/history/black-history/t-hutton-mills-jnr.

Tsang, L., E. Njoku, and J. A. Kong. “Microwave Thermal Emission from a Stratified Medium with Nonuniform Temperature Distribution.” Journal of Applied Physics 46, no. 12 (December 1975): 5127–33.

University of Nigeria. “University of Nigeria Staff Profile - Prof. Animalu Alexander O.E.” Accessed April 6, 2022. http://www.unn.edu.ng/internals/staff/viewProfile/NDQw.

Urama, Johnson O., and Jarita C. Holbrook. “The African Cultural Astronomy Project.” Proceedings of the International Astronomical Union 5, no. S260 (January 2009): 48–53.

Wardale, J. R. Clare College. University of Cambridge - College Histories. London: F. E. Robinson and Co., 1899.

WGBH Educational Foundation. “Emmanuel M. [Sic.] Obiechina.” WGBH - Forum Network. Accessed April 11, 2022. https://forum-network.org/speakers/obiechina-emmanuel-m/.

Yale Class of 1965. “Orde Musgrave Coombs.” Yale Class of 1965. Accessed May 19, 2022. https://yale1965.org/orde-musgrave-coombs/.