Remembering VE Day

The 80th anniversary of VE Day on 8 May this year marked eight decades since the end of World War II in Europe. Clare News spoke to three alumni about their memories of growing up during the war, of VE Day itself, of National Service, and of coming up to Clare in the aftermath of war.

Peter Duncomb (1950) read Natural Sciences at Clare and enjoyed a lengthy career at Tube Investments, a research and manufacturing company.

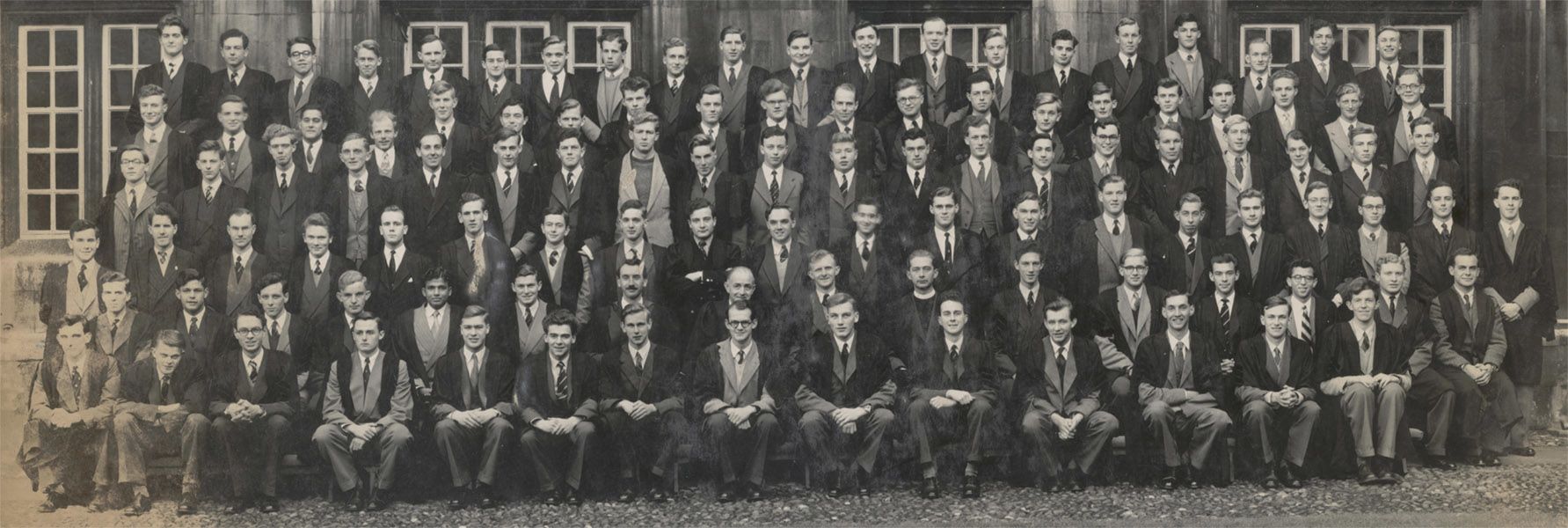

1950 matriculation (photo by Lafayette Photography)

1950 matriculation (photo by Lafayette Photography)

Clive Bradley (1955) read Law at Clare and worked in broadcasting, newspaper and book publishing. He was awarded a CBE in 1996 for services to publishing.

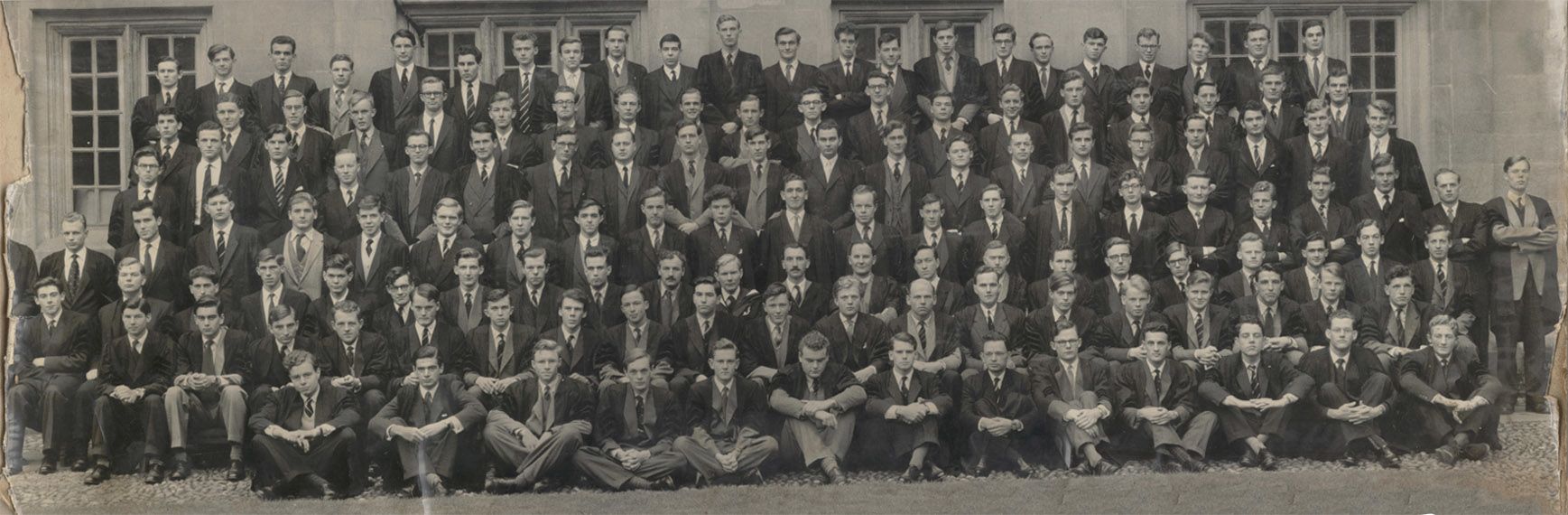

1955 matriculation (photo by Lafayette Photography)

1955 matriculation (photo by Lafayette Photography)

Brian Austin (1958) read English at Clare and went into the Commonwealth Relations Office straight after graduating before a long career in the British diplomatic service.

1958 matriculation (photo by Lafayette photography)

1958 matriculation (photo by Lafayette photography)

Growing up during the war

Peter: “I grew up in East London during the war.

My father owned a news agency, and I remember

him spending countless nights delivering papers

to Fleet Street. In 1939, when I was just eight

years old, I was sent away to boarding school in

Teignmouth, far from the turmoil in London. My

father was exempt from military service because

of his job, but one night I vividly recall him driving

home, only to be stopped by a policeman who

told him he’d just driven over a bomb. There was

also the time when a bomb exploded in the

garden next door, leaving a huge 20-foot crater.

Thankfully, no one was hurt. Then there were the

flying bombs—the V1s. The sirens would often be

a bit slow to alert us, so we’d see the red flame

disappearing on the horizon before we even

heard the warning sounds. The V2 rockets were

worse—completely unpredictable. One landed

just half a mile away from us, I remember cycling

over to check out the wreckage.”

Clive: “Living in south Essex near a Battle of Britain air base and under bombing flight paths from Germany meant that by day and night you were anxiously protected from potential danger. Parents invested in various types of air raid shelter, and I would usually be bedded down in the cupboard under the stairs, thought to be safer if the house was bombed. Air raid warnings day and night were frequent, and you were supposed to go into the nearest shelter. Small boys like me liked to stay in the open to see the planes – British or Nazi – with anxious mothers desperately calling us inside.”

Brian: “Mother with my older brother and I evacuated from South London to Pembrokeshire in September 1940. We stayed with a railway engine driver and his wife, and with nothing else to do, mother took us out for long walks. Father, a temporary wartime civil servant with the Admiralty came to see us at Christmas. By March, mother could stand it no longer, and we came back to Streatham, in time for the biggest bombing raids of the Blitz in May 1941. My brother and I would go out the morning after the raids to see if we could find any good bits of shrapnel.”

VE Day

Peter: “I don’t have particularly strong memories of VE Day. I was at Oundle School at the time, far from London, and when the announcement came, I was actually allowed to go home. There was a sense of relief, of course, but it wasn’t the huge celebratory explosion you might expect. It felt more like a quiet moment of acknowledgment. The war had taken so much from so many, and while victory was a cause for celebration, it also came with a quieter sense of reflection.”

Brian: “On VE day there was a big party and bonfire at the open end of our road near the railway where there were no houses. The bonfire melted the tarmac on the road. For the first time, we did not have to close the blackout curtains.”

Clive: “The first excitement came with the battle of El Alamein in 1942, seen as the prelude to eventual victory, supported by the entry of the US into the war at the beginning of that year. This was followed by the campaign through Italy and the collapse of the Mussolini government, though the Nazis took over with renewed ferocity. D-Day itself remained secret until it occurred, and the manpower losses were never fully reported. We all eagerly followed the progress through northern France into Germany. By the time of the Nazi surrender we were punch drunk. At my boarding school we were not given the national holiday in celebration as apparently our work was not up to standard – I suspect the real reason was that the school had no idea what to do with us.”

National Service

Peter: “My time in National Service is a chapter I look back on with a lot of fondness. I joined the Air Force and, from the start, it was incredibly disciplined, but I enjoyed every moment of it. I spent 18 months in pilot training, I was stationed at RAF Wittering for a time, where I learned to fly across England in a Percival Prentice, followed by a Harvard. I kept a log training book that shows all the flights I made, which I still have today. My last flight was in 1950, and by then, I’d completed 200 hours of flying. I was lucky to have the role I did. Not everyone had the same experience in National Service, but for me, flying became a passion I would never forget.”

Clive: “Young men had no choice – they were conscripted for 18 months, lengthened to two years on the outbreak of the Korean War. I was lucky – I was commissioned in the RAF. After fairly tough recruit and officer training, I served as adjutant of a large training wing, responsible for basic admin, living happily in relative luxury in the Officers’ Mess. The intake of servicemen and women seemed happy as well and for most of the time life was pleasant – there didn’t seem much danger of conflict at the time.

National Service had some social advantages for us. We public school boys, with better chances of being commissioned, probably thought ourselves a little superior, but at the same time, particularly but not only during recruit training, we were mixed with all and sundry and learnt about the living conditions and family lives of people with very different upbringings.”

Brian: “I was called up in September 1956, having deferred from March till the end of the school year on my headmaster’s advice – a bad mistake. I went into the RAF and ended up as a radar operator posted to a new NATO radar unit in an isolated part of Western Germany. Our task was to monitor the air traffic on the corridors to Berlin and activity in East German airspace. The work was boring but demanding, somebody misread the height of an unidentified plane and set alarm bells jangling throughout NATO. The residential camp with our barracks was some 10 miles from the radar site. We were bussed each day usually in unheated lorries to a vast bunker deep under a hill with a large radar aerial sweeping round on top surrounded by nodding height radars. We worked in shifts, and I came to prefer the long night shift. Watching the radar screen, we did 2 hours on and 2 off. Alertness could only be maintained for 2 hours at a time.”

Transition to Clare

Peter: “The transition from National Service to College was a quick one—just four days after finishing with the RAF, I came up to Clare. It was quite a shift, much more laid back than the discipline of the Air Force, though there was still the regimented dinners in Hall that kept a bit of order. Most of my peers had also done National Service, so we had plenty of stories to swap about our varied experiences. We were free to enjoy college life, but we were sensible about it too. I had a room in Old Court when I first arrived but later moved out to Chesterton Lane. College life had its own rhythm, and I thoroughly enjoyed playing rugby and Eton Fives. Despite the change in pace, I didn’t give up flying. I joined the RAF Volunteer Reserves and continued to fly out of Marshalls. I managed to clock up 40 hours during the year, keeping that passion alive while balancing the demands of a degree in National Sciences.”

Clive: “After the adult experiences of National Service, it was like regressing to school, but with a slightly more independent lifestyle. All first-year undergraduates were housed in the rather bleak Memorial Court with gas fires and cottage loaves provided by gyps, with the near compulsory First Hall at the early hour of 6pm, and the strange requirement when out for the evening to be back in college by midnight. We were in statu pupilari, and the College did not want us to go astray, which at least got some essays done.

Refreshing the habit of learning was not as difficult as was sometimes made out. As the weeks progressed, minor forms of independence reasserted themselves. It was, after all, a highly privileged life, and most of us knew it.”

Brian: “National Service ended in December 1957 and those born after November 1939 escaped it. We who were already in did our full 2 years, so I came out in September 1958 with less than a month to get organised before coming to Clare in October. I went from one highly structured all-male organisation to another, much nicer, highly structured all-male organisation. Swapping a bed space in a barrack room in which there were 9 other men for a historic room on C staircase in the heart of Old Court was a plus. Formal Hall every weekday evening was on a different plane, both for food and ambience, from lining up in the cookhouse. After having to sign out and in every time I left our high security camp, the freedom to come and go was enormous, even if the gates were closed at midnight. I had worn uniform for 2 years; wearing a gown to lectures, supervisions, hall and when going out after dark was no problem, even perhaps a little secret source of pride. After the social, intellectual and cultural desert of an isolated radar unit, Cambridge was an explosion of opportunity which I was determined to make the most of.”